Table Of ContentVictorian Popularizers of Science

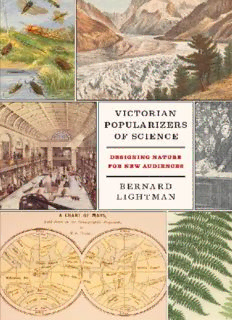

Victorian Popularizers of Science

Designing Nature for New Audiences

B E R N A R D L I G H T M A N

TheUniversityofChicagoPress

chicago and london

bernard lightman isprofessorofhumanitiesatYork

University,Toronto.HeisauthorofTheOriginsofAgnosticism,

editorofVictorianScienceinContextandthejournalIsis,and

coeditorofFiguringItOutandScienceintheMarketplace.

TheUniversityofChicagoPress,Chicago60637

TheUniversityofChicagoPress,Ltd.,London

©2007byTheUniversityofChicago

Allrightsreserved.Published2007

PrintedintheUnitedStatesofAmerica

161514131211 10090807 1 2 3 4 5

isbn-13:978-0-226-48118-0(cloth)

isbn-10:0-226-48118-2(cloth)

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

Lightman,BernardV.,1950–

Victorianpopularizersofscience:designingnaturefornewaudiences/

BernardLightman.

p. cm.

Includesbibliographicalreferencesandindex.

isbn-13:978-0-226-48118-0(cloth:alk.paper)

isbn-10:0-22648118–2(cloth:alk.paper) 1. Science—Great

Britain—History—19thCentury. 2. Technicalwriting—Great

Britain—History—19thCentury. 3. GreatBritain—Socialconditions—

19thcentury. I. Title.

Q127.G4L54 2007

509.41(cid:1)09034—dc22

2007015179

(cid:3)∞Thepaperusedinthispublicationmeetsthe

minimumrequirementsoftheAmericanNational

StandardforInformationSciences—PermanenceofPaper

forPrintedLibraryMaterials,ansiz39.48-1992.

Contents

Preface (cid:1) vii

Acknowledgments (cid:1) xiii

chapter one (cid:1) 1

Historians,Popularizers,andtheVictorianScene

chapter two (cid:1) 39

AnglicanTheologiesofNatureinaPost-DarwinianEra

chapter three (cid:1) 95

RedefiningtheMaternalTradition

chapter four (cid:1) 167

TheShowmenofScience

Wood,Pepper,andVisualSpectacle

chapter five (cid:1) 219

TheEvolutionoftheEvolutionaryEpic

chapter six (cid:1) 295

TheSciencePeriodical

ProctorandtheConductof“Knowledge”

chapter seven (cid:1) 353

PractitionersEntertheField

HuxleyandBallasPopularizers

chapter eight (cid:1) 423

ScienceWritingonNewGrubStreet

conclusion (cid:1) 489

RemappingtheTerrain

Bibliography (cid:1) 503

Index (cid:1) 535

Preface

in 1875 an article appeared in the Saturday Review harshly condemning

those“scatter-brainedauditors”whofrequentedtheRoyalInstitutiontohear

lecturesaboutscience.Theanonymousauthordividedsuchaudiencesinto

twotypes.Onegroupdabbledinscience“outofshiftingcaprice,orindef-

erence to the dictates of fashion.”Another group attended lectures“with

the best and steadiest intentions,” but they were “incapacitated by lack of

general education from grasping any special subject.”The author’s low

opinion of the audience for science lectures was matched by an equally

dismal evaluation of what they heard. “It is to accommodate such feeble

votaries,” the Saturday Review critic declared, “that ‘popular science’ has

beeninvented.”Althoughtheauthoracknowledgedthattherewerebenefits

to“realsciencefrombeingfashionableandpopular,”neverthelessitshard

factscouldnotbeexpectedto“retainthefavourofthemultitude.”“Realsci-

ence”thereforeuseda“counterfeit”to“standforituponpublicplatforms”

in order to secure the “patronage of the vulgar.” Popular lecturers tended

to“garnishtheinformation”theyconveyedtotheiraudiencewith“rhetor-

icalflourishes”andtostresspeculiar,sensational,andstrangephenomena

rather than those that were intrinsically important. The popular lecturer

hada“strongpropensityforparadox”andsoughtto“surpriseandastonish

hisauditors.”Inordertoillustratethemostabstrusepointsofthelecture,

thespeakerreferredto“familiarobjectsandcircumstances”thatseemedto

illuminatethesubjectbutintheendmerelymuddledit.1

1.“SensationalScience”1875,321

vii

viii preface

Intheopinionofthisauthor,itwasreallya“hopelesstask”toattemptto

make“sounddisquisitionsonanyscientificsubjectthoroughlyintelligible

tothosewhohavenotundergonespecialtraining,unlesstheyhavereceived

athoroughgeneraleducation.”Conveyingscientificinformationtoanun-

informed reading public was doomed to failure. It created two unwanted

creatures, the dilettante and the incompetent lecturer. As to the first, the

Saturday Review critic denied that “sensational science” advanced the cul-

tureoftheage.Aliterarydilettantewastolerable,buta“dilettanteinscience

proudtomakesmall-talkoutofHuxley’sorTyndall’slectures,inflatedwith

fallacies of his or her own extraction...is a social pest.” Worse still had

beenthecreationoftheincompetentlecturerwhomerelyimitatedthedra-

matic lecturing styles of Thomas Henry Huxley or John Tyndall without

possessing their expertise. The existence of incompetent lecturers was a

“collateral evil entailed by the really competent teachers catering for the

frivolous and illiterate.” Under the present system “anybody of sufficient

socialstandingtodrawanaudienceconsidershimselfentitledtoholdforth

atpennyreadings,Mechanics’Institutes,andsoforth,onscientificsubjects

perfunctorily crammed up for the occasion.” There was only one “right

way”toinstill“ahealthyenthusiasmforscienceintoallclassesofsociety,”

thecriticinsisted.Therepresentativesofsciencehadto“exhibitthemselves

intheirtruecharacter,andtoabandonallthemeretriciousallurementsof

thaumaturgyand‘sensation.’”Theyhadtomakethepublicunderstandthat

the“genuinepursuitofscientifictruthisworkandnotplay.”2 Ifthecritic

fromtheSaturdayReviewhadhadhisway,onlythemenofsciencewouldbe

permittedtocommunicateknowledgetogeneralaudiences,andtheywould

makenoconcessionstothepublic’srudimentarylevelofunderstanding.But

who,exactly,werethepurveyorsof“sensationalscience”?Thecriticnever

mentionsanybyname.Wasthereanarmyofthemoronlyahandful?Were

they really as pernicious to the cause of scientific truth as this journalist

claimed?

Thisbookexaminesthosepopularizerswhooffered“sensationalscience”

totheBritishpublicinthesecondhalfofthenineteenthcentury.Theemp-

hasisisonthosewhowerenotpractitionersofscience.Manyofthemwere

professional writers and journalists. The overwhelming majority of them

weremembersoftheeducatedmiddleclass.Therewereasignificantnumber

ofthem.Idealwithoverthirtyofthesefigures.Icouldeasilyhaveincluded

2.Ibid.,322

preface ix

manymore,butIhavechosentolimitmyselftothemostprolific,themost

influential, and the most interesting among them. They assumed the role

of interpreters of science for the growing mass reading audience in this

period.Ido notattempttoanalyze thisaudience ingreat detail.Iam more

concernedwithhowthepopularizersconceivedoftheiraudienceandhow

thisconceptionaffectedthewaytheywroteandlectured.Theysawthem-

selves as providing both entertainment and instruction to their readers.

Cognizant that they were operating in a market environment, they con-

sidered the use of “thaumaturgy” as a necessity for those who wished to

be a commercial success. Some were extremely successful, producing best

sellers that were as widely read as the Origin of Species or the other key

scientifictexts of the day. For many of these popularizers, nature was full

of meaning, charged with religious significance. They looked back to the

natural theology tradition and in their writings offered new audiences a

vivid glimpse of the design they perceived in nature. Since they were in-

fluential, and since their interpretation of the larger meaning of scientific

ideas was often at odds with the agenda of elite scientists, they cannot be

ignored. Any attempt to investigate how the British understood science in

the second half of the century must take them into account. By focusing

onBritainIcanexaminethedevelopmentofsciencewritingandlecturing

forabroadaudienceinacountrythatwasamongthefirsttoexperiencea

communicationsrevolution.

Thisbookisdividedintoeightchapters.Ibeginwithachapterthatsets

the scene. Here I explore the transformation of the publishing scene, and

how it intersected with the changing world of science. I consider why the

scienceswerethoughttobeespeciallyimportantandexcitinginthesecond

halfofthecentury—whythisperiodissometimesreferredtoastheageof

the worship of science. I discuss the traditions of science popularization

that were important from the late eighteenth through the first half of the

century. The varied approaches adopted by scholars to study popularizers

ofVictoriansciencearealsoanalyzed.

In the next two chapters I examine two distinct groups of popularizers

activeinthesecondhalfofthecentury.Chapter2centersonthelargenum-

ber of Anglican parsons who wrote about science for the general reader,

including Ebenezer Brewer, Charles Alexander Johns, Charles Kingsley,

Thomas William Webb, Francis Orpen Morris, George Henslow, and

WilliamHoughton.Thiswasoneofthegroupsthatwould-beprofessionaliz-

erslikeThomasHenryHuxleyweretryingtopushoutofscience.Through

their work the Church of England maintained an active presence in the

Description:The ideas of Charles Darwin and his fellow Victorian scientists have had an abiding effect on the modern world. But at the time The Origin of Species was published in 1859, the British public looked not to practicing scientists but to a growing group of professional writers and journalists to interp