Table Of ContentT H E L O N E L Y S K Y

by WILLIAM BRIDGEMAN

and JACQUELINE HAZARD

Illustrated with Photographs

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY • NEW YORK

Copyright, 1955, by Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this

book or portions thereof in any form.

In Canada, George J. McLeod, Ltd.

First Edition

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 54-10518

THE LONELY SKY has been given security clearance by the U. S. Navy and

the U. S. Department of Defense.

The publisher wishes to thank the Douglas Aircraft Company, Inc., for

permission to use the photographs reproduced in this book.

81979-0115

Printed in the United States of America

Dedicated to the memory of

CAPTAIN NORMAN “BUZZ” MILLER, USN;

Commanding Officer of Bombing Squadron 109,

“The Reluctant Raiders”

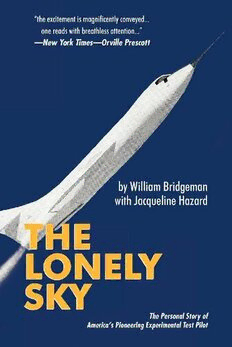

William Bridgeman. Photo courtesy of Douglas Aircraft Company, Inc.

CONTENTS

Prologue 7

Chapter I 12

Chapter II 16

Chapter III 23

Chapter IV 30

Chapter V 39

Chapter VI 52

Chapter VII 63

Chapter VIII 76

Chapter IX 86

Chapter X 101

Chapter XI 112

Chapter XII 120

Chapter XIII 141

Chapter XIV 161

Chapter XV 179

Chapter XVI 187

Chapter XVII 195

Chapter XVIII 214

Chapter XIX 234

Chapter XX 249

Chapter XXI 261

Chapter XXII 270

Chapter XXIII 282

P R O L O G U E

T

his is the story of an experimental high-speed airplane and the test pilot who

flew it.

The story of America’s experimental airplanes, the supersonic

pioneers, could begin in the dawn of a summer day above a German

countryside. The year is 1942.

Out of the brightening sky an unarmed, stripped-down Mosquito,

cameras whining, shot in low over the remote Nazi airstrip. The RAF

officer again noticed the many peculiar-looking black streaks at the end

of the runway; some as even as railroad tracks. Seconds later the little

bomber disappeared into the west.

At Medmenham the developing laboratory of the RAF Photo

Interpretation Unit verified the news once more. The Germans were

busily experimenting with something radically different from anything

the Allies had in the air—probably rockets and rocket-propelled

aircraft. And there was little doubt, the even, parallel streaks were

burned by the flames from a twin-jet fighter.

The United States had no such weapons. Upon our entry into the

war a high-level decision was made. Only a fraction of our resources

would be devoted to jet and rocket research. Time and men and

money would be used to pour out and perfect more of what we had

going already. The huge production machine would be uninterrupted

while the conflict lasted.

But with the news from Medmenham, added to the top of the pile

of intelligence reports from other sources, General Hap Arnold, chief

of the Army Air Forces, appointed a special committee of scientists and

engineers in the allied fields of aerodynamics to advise him on the

future of aircraft and aircraft weapons. He particularly asked the

committee to think about the aircraft not only of tomorrow but of 20

years from then. To head his advisory committee he chose, on the

advice of his close friend Robert Millikan of the California Institute of

Technology, a member of Millikan’s staff, Dr. Theodore von Karman.

As head of Arnold’s Scientific Advisory Board, von Karman, a long-

time prober of supersonics and a strong advocate of applying its

principles to the design of aircraft, began to explore the possibilities of

a truly supersonic airplane.

At the same time the military services were demanding that

manufacturers produce tactical aircraft capable of reaching speeds of

400 mph. The designers were handed the sizable task of molding a

shell sleek and strong enough to reach this speed with the available,

puny reciprocating engine.

It was true we had access to a jet engine. But it wasn’t much more

powerful than the engines we had already and it ate up twice the fuel.

General Electric had put it together, at General Arnold’s request, from

plans of the British Whittle engine brought secretly into the country by

Arnold in 1941. Arnold gave the job of wrapping a frame around the

G.E. turbo-jet attempt to the young and enterprising Bell Company.

The result was America’s first jet, the P-59. It flew valiantly enough

late in 1942, but according to Arnold’s own account of the

experimental ship, its “legs weren’t long enough” to successfully reach

a target. The model never got into combat.

Arnold turned back to the “right-now” aircraft. He listened to the

problems of the manufacturers who were successfully turning out the

faster ships he had demanded. He talked to the combat pilots who flew

the high-performing planes that were now coining off the line by the

thousands.

“What can we do to improve performance?” he asked his fighter

pilots.

“They’re pretty hot right now, sir. If you make them any faster we

won’t be able to fly them. I dove my Mustang on an ME-109 last week …

the controls froze up on me and she shook like a rivet handle. I

couldn’t pull her out of it. I was a fast thousand feet from the bottom

before I could get the nose up.”

A new problem. In the airplanes that reached the 400-mile-an-hour

mark demanded by the military, pilots, diving in combat, were

running into the raw edge of the speed of sound. (Mach 1), into the air-

monster, “compressibility,” a phenomenon that eventually became

more romantically known as the sound barrier.

The Germans and the Japs were not the only enemy that the fighter

pilots had to face. There was the reef of the sound barrier, the dark

area of speed where compressibility lurked to shake a plane to pieces

or suck it out of control straight down into a hole in the ground.

An effect of high speed, compressibility was a phenomenon known

to the aerodynamicists in theory for many years. Because of this

phenomenon, it was generally agreed that flight at and beyond the

speed of sound was impossible.

However, as a result of combat demands, aircraft had flown right

into the monster and the scientists were caught with no answers. In

order to get the answers, investigations into high speed were urgently

needed. This need for all-out research into the unexplored area where

compressibility lay was apparent to the aircraft industry, the Air Force,

the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics, and the nation’s aeronautical research

establishment, the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics.

It also became apparent that new tools to investigate the area were

needed. Methods of reaching speeds where compressibility could be

studied just didn’t exist. Wind tunnels “choked” as speeds reached that

of sound. Test pilots could dive into such transonic speeds, but it was

too dangerous. There was only one answer: full-scale, high-speed

experimental models, fitted with instrumentation recording devices, to

fly in nature’s big laboratory, the sky; airplanes that would do in level

flight what had only been done in dives.

When things began to look pretty good in Europe, General Arnold

became a champion of the “research-airplane” idea. By the end of 1943

the Navy, the Air Force, and NACA held conferences at NACA

headquarters in Washington to discuss the feasibility of such research

airplanes.

Pursuing a slightly different course, Dr. von Karman’s Scientific

Advisory Board had already stimulated the Air Force’s interest in the

long-range research approach to a supersonic airplane. General F.O.

Carroll, in informal sessions with manufacturers, had brought up the

idea of such an aircraft, not so much as an exploratory tool as an

attempt toward a conventional-operating ship capable of supersonic

speed in actual flight. Douglas Aircraft Company picked up the

challenge and with their own resources assigned their then-small

research-design group to come up with something. The project

became known as X-3.

A year later, toward the last days of the war, Germany got her V-1

rockets and her jet-powered ME-262 and rocket-propelled ME-163B

into the air. But they were too late. They were a futile attempt, a final

bid; and their appearance caused more wonder than destruction.

The war in Europe was over. It was then that the final decision was

made to go ahead with the hurry-up research-airplane program. Two

projects were ordered: the Bell X-1, sponsored by the Air Force, and the

Douglas D-558, sponsored by the Navy. Both projects were eventually

to be tools that would enable NACA to find out all about high-speed

flight.

The X-1, fitted with a rocket engine, was to fly briefly at transonic

speed; while the D-558, using a turbo-jet engine, was designed to

explore, for a longer period, in the high subsonic range.

On V-J Day a group of Navy, NACA, and Douglas engineers met in a

conference room of the nearly deserted El Segundo plant to work out

the details of the D-558. A year had passed since Ed Heineman’s El

Segundo staff had been offered the idea of the original experimental

research plane. In that time advantages of the swept-back wing in

cutting down compressibility were picked up from Germany after V-E

Day.

The Navy project became two airplanes: the Phase I straight-winged

D-558 and the Phase II D-558. The D-558-II utilized the swept wing

and, in addition to the turbojet engine, it was equipped with a rocket

engine similar to that in the Bell X-1. She was named Skyrocket.

Sometime later the Air Force signed a contract with Douglas to go

on investigating with their X-3 project the possibilities of a true

supersonic airplane. The X-3 was eventually ordered in 1949, to be

added to the small stable of weird-shaped Navy- and Air Force-