Table Of ContentTh e Haitian Declaration

of Independence

Jeff ersonian America

JAN ELLEN LEWIS, PETER S. ONUF,

AND ANDREW O’SHAUGHNESSY, EDITORS

Th e Haitian Declaration

of Independence

Creation, Context, and Legacy

EDITED BY JULIA GAFFIELD

University of Virginia Press

CHARLOTTESVILLE AND LONDON

University of Virginia Press

© 2016 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2016

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Haitian Declaration of Independence : creation, context, and legacy / edited by

Julia Gaffi eld.

pages cm.—(Jeff ersonian America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

isbn 978-0-8139-3787-8 (cloth : acid-free paper)—isbn 978-0-8139-3788-5 (e-book)

1. Haiti—History—Autonomy and independence movements. 2. Proclamations—

Haiti—History and criticism. 3. Liberty—Political aspects—Haiti—History—19th

century. 4. Dessalines, Jean-Jacques, 1758–1806. 5. Haiti—History—Revolution,

1791–1804. 6. Haiti—History—1804–1844. I. Gaffi eld, Julia.

f1924.h22 2015

972.94(cid:2)04—dc23

2015008544

Publication of this volume has been supported by the Thomas

Jeff erson Foundation.

Contents

Preface vii

Acknowledgments xi

Introduction: The Haitian Declaration of Independence

in an Atlantic Context 1

DAVID ARMITAGE AND JULIA GAFFIELD

PART I(cid:2)Writing the Declaration

Haiti’s Declaration of Independence 25

DAVID GEGGUS

“Victims of Our Own Credulity and Indulgence”: The Life of

Louis Félix Boisrond- Tonnerre 42

JOHN GARRIGUS

The Debate Surrounding the Printing of the Haitian Declaration

of Independence: A Review of the Literature 58

PATRICK TARDIEU

Living by Metaphor in the Haitian Declaration of Independence:

Tigers and Cognitive Theory 72

DEBORAH JENSON

PART II(cid:2)Haitian Independence and the Atlantic

Law, Atlantic Revolutionary Exceptionalism, and the Haitian

Declaration of Independence 95

MALICK W. GHACHEM

vi(cid:2)CONTENTS

Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Norbert Thoret, and the Violent Aftermath

of the Haitian Declaration of Independence 115

JEREMY D. POPKIN

Did Dessalines Plan to Export the Haitian Revolution? 136

PHILIPPE GIRARD

PART III(cid:2)Th e Legacy of the Haitian Declaration of Independence

“Outrages on the Laws of Nations”: American Merchants and Diplomacy

after the Haitian Declaration of Independence 161

JULIA GAFFIELD

The Sovereign People of Haiti during the Eighteenth

and Nineteenth Centuries 181

JEAN CASIMIR

Thinking Haitian Independence in Haitian Vodou 201

LAURENT DUBOIS

Revolutionary Commemorations: Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Haitian

Independence Day, 1804–1904 219

ERIN ZAVITZ

Appendix: The Haitian Declaration of Independence 239

Bibliography 249

Notes on Contributors 267

Index 269

Preface

Index and middle fi nger crossed, the American political commentator Rachel

Maddow informed viewers of her April 1, 2010, MSNBC primetime show,

“us and Haiti, we’re like this. We always have been.” At fi rst glance, this

may seem like a throwaway comment worthy of a raised eyebrow; in fact,

Maddow’s reference to the interconnected histories of Haiti and the United

States refl ects a transformation in the fi eld of Atlantic history.¹ Scholars rec-

ognize the American, French, and Haitian Revolutions as part of a broader

set of changes occurring across the Atlantic World.

This historiographical shift could be seen most explicitly in a recent ex-

hibition at the New-York Historical Society, Revolution! The Atlantic World

Reborn (November 11, 2011–April 15, 2012), which focused on the material and

symbolic connections between the three revolutions. At this exhibition, the

Haitian Declaration of Independence was put on display for the fi rst time.

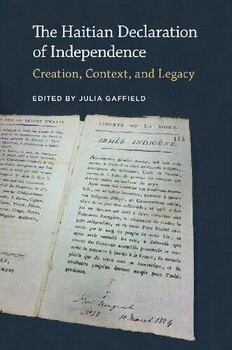

The newly independent Haitian government printed this document less

than three weeks after Jean-Jacques Dessalines delivered its text as a speech

on January 1, 1804. The printed version was to be distributed to the powers of

the Atlantic World. “And then, in a very sad twist of fate,” Maddow reported,

“every known copy of it disappeared. For the next two hundred years, the

Haitian Declaration of Independence was reprinted in newspapers and in

handwritten duplicates. But the actual document itself, the actual, original

eight-page pamphlet, the physical representation of Haitian independence

was lost.”

In February 2010, I discovered one of the original government-printed

versions of the declaration in the Jamaican records at The National Archives

of the United Kingdom in London. At the time, I thought this to be the only

extant copy. Just over a year later, however, I discovered another printed copy

in the Admiralty records of the same archives. This time the declaration was

printed as a broadside. These documents are the only known remaining offi -

cial copies of the Haitian Declaration of Independence. The text of the docu-

viii(cid:2)PREFACE

ment was well known, but a signed manuscript original or an offi cial printed

copy did not exist in Haiti or elsewhere, historians believed.

The presence of the documents in London tells a story of international

communication in the early months of Haiti’s independence. The procla-

mation announced to the nations and empires of the Atlantic World that the

territory was no longer under French authority; instead, the new “Haytian”

government ruled it. Haitians leaders knew that independence from France

could only be complete if foreign governments recognized and supported

the new nation.

The document circulated around the Atlantic, and portions of it were re-

printed in newspapers in cities like Philadelphia and London, and even as

far away as Bombay. The international reception of this document, however,

was mixed. Some readers were sympathetic and saw Haitian independence

as the justifi able reaction to French cruelties. Others, however, were terrifi ed

by the implications that this success might mean for their own nation’s col-

onies and personal property. Would the Revolution spread? was the question

on everyone’s mind.

Several weeks before I discovered the document, a magnitude 7.0 earth-

quake devastated Port-au-Prince and the surrounding area. The world’s at-

tention was on Haiti, as it often is when that nation is in crisis. Media outlets

around the world, like the Rachel Maddow Show, published digital copies of

the Haitian Declaration of Independence, marking the fi rst time many peo-

ple read or saw the document. They responded with interest and intrigue—

and sometimes with hostility. Much of the hostility came from readers who

compared the Haitian document against its American equivalent; the Hai-

tian Declaration of Independence is a call to arms that expresses hatred and

eternal vengeance toward the French. Many commenters also wanted to see

the roots of Haiti’s contemporary problems in its founding document, par-

ticularly in the context of American televangelist Pat Robertson’s claim that

Haitians had “sworn a pact with the devil.”²

Haiti was one of the fi rst countries in the world to issue a declaration of

independence after the United States. The American Declaration of Indepen-

dence, David Armitage writes, “provided the model for similar documents

around the world that asserted the independence of other new states.”³ In-

deed, when the revolutionary forces in the French colony of Saint-Domingue

defeated Napoléon’s troops, they followed the United States’ lead in proclaim-

ing their determination to “live free or die”—choosing the words “liberté ou

la mort” for the state letterhead and the title of their Acte de l’Indépendance.

However, while the Haitian leaders drew distantly on Jeff erson’s document

for inspiration—an earlier draft of the declaration based on his original had

PREFACE(cid:2)ix

been rejected as too tame for the task—they tailored their own words to the

circumstances at hand. Thus, the two documents are distinctly diff erent yet

clearly connected in motivation, meaning, and genre.

As part of its Revolution! exhibit, the New-York Historical Society put the

Haitian Declaration of Independence on display along with the Stamp Act

(1765), John Greenwood’s Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam (1752–1758),

Thomas Clarkson’s “African Box,” and other documents, paintings, and ob-

jects that symbolized the interconnected Age of Revolution. In conjunction

with the exhibit, the society hosted a symposium entitled, “The Age of Rev-

olution: A Whole History,” on January 21, 2012. The goal of this symposium

was to better understand the unique characteristics of each revolution as well

as the common threads that wove them together. During this conference, I

had the good fortune of meeting historian David Armitage, and during our

conversation he inspired and encouraged me to pursue a collaborative study

of the Haitian Declaration of Independence.

With this in mind, on March 7–8, 2013, the Robert H. Smith Interna-

tional Center for Jeff erson Studies (ICJS), under the direction of Andrew

O’Shaughnessy, sponsored and hosted the conference “The Haitian Decla-

ration of Independence in an Atlantic Context.” The ICJS seeks to support

the study of Thomas Jeff erson and his legacy through interdisciplinary and

innovative research. While the US Declaration of Independence was the fi rst

of its kind, the Haitian document helped to confi rm it as a genre; the Hai-

tian Declaration of Independence, therefore, is a crucial part of the legacy of

the American document. The eff orts of the ICJS to expand the scope of its

research beyond continental early America refl ects a series of historiograph-

ical interventions that highlight the interconnectedness of the early modern

Atlantic World, particularly during the Age of Revolution. Scholars have also

begun to situate Haiti at the center of the Age of Revolution and to look

beyond its revolution in order to appreciate the context, character, and devel-

opment of Haiti as an independent nation.

The essays in this volume are by leading scholars in the fi eld and aim to

provide a better understanding of the internal and external infl uences that

shaped the world’s second successful declaration of independence. How

tightly and in what ways was the Haitian Declaration of Independence in-

tertwined with its American predecessor? What shared aspects of the Age

of Revolution were articulated in the Haitian document? What distinctive

features were added and what elements were omitted? And how can a focus

on these documents provide a point of entry for a discussion about the larger

questions of meaning and signifi cance in the Atlantic revolutions? As the

product of the only successful slave revolution in the world, the Haitian Dec-