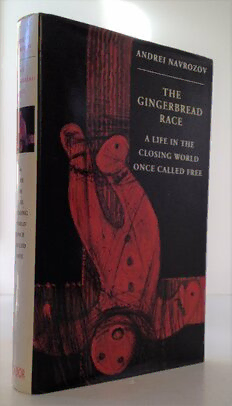

Table Of ContentANDREI NAVROZOY

TFIE,

GINGERBRE,AD

RACE

A LIFE IN THE

CLOSING WORLD

ONCE CALLED FREE

PICADOR ORIGINAL

A Picador original

First published 1993 by Pan Books Limited

a division of Pan Macmillan Publishcrs Limited

Cavaye Place hndon SWIO 9PG

and Basingstoke

Associated companies throughout the world

ISBN 0 330 376368

Cnpyright @ Andrei Nawozov 1993

Thc right of Andrei Nalrozov to be identifed as the

author of this work has been asscrtcd by him in accordance

with the C-opy.tght, Designs and Patents Acr 1988.

AII righa reserved. No reproducrion, copy or transmission

of this publication may bc made without writtcn pcrmission.

No pragraph of this publicadon may be reproduced, copied or

nansmined save wirh wrinen permission or in accordancc with

the provisions of the C,opltight Act 1956 (as amendcd). Any

pcrson who does any unauthorized act in relation to

this publication may be liablc to criminal prosccution

and civil daims for damagcs.

L35798642

A CIP catdogue record for this book is available from

the British Library

Desigred by Hayley Cove

Typeset by Cambridgc Composing (UK) Limitcd, Cambridge

Printed by Mackays of Chatham plc, Kent

I do not say to people yw an to be forgioen or confumncd,

I say to themyu,t are dying.

- Arthur de Gobineau to Alexis de Tocqueville, 1856.

PART ONE

OUT

OF PARADISE

t

The sun sets and lengthens the shadow on the dial. I understand what

this means because time is so easily read. It is a culture. In the

language to which I was born, it is the Sanskrit word for the track of

the wheel, left in the dust of the ritual chariot races, aartanna, a

millennium before the birth of Plato. The atavistic spokes on the face

of a clock are remnants of its revolutionary past. It passes, and an

artist composes a still life of ripe fruit on the wooden planks of a rustic

table. Now it is early morning. As he begins painting, his light changes

and declines. His hand, even if it is a hand of genius, is no match for

his honesty. Hence his yearning for the ideal, which alone captures

time, for in order to depict subjects in their true light he must know

their ultimate destiny. Let us rejoice. This yearning runs from our

purest Indo-European wellsprings, and it alone makes the present

worth living. But now the chariot wheel is in its last revolution. Then

let us mourn, because the aartanna of Western civilization is not

eternal. Another culture is on the move, and with our own dying eyes

we may yet see what sort of imprint it leaves on the asphalt. From

where I write, it looks like the caterpillar track of an armoured

personnel carrier. The artist may protest, as the still life before me

could not have seemed more picturesque. Yet I now commend it into

his hands, for he alone exhibits a vital interest in the ultimate destiny

of such subjects as ripe fruit, Iiarthingales and individual liberty.

2

If power is a culture, then Vnukovo was the Pieria of its muses. But

this hardly captures the glamour. [f Moscow is the Hollywood of

power, Vnukovo was Beverly Hills. But this empties it of the mystery.

IHE GTNGERBREAD RACE

Moscow was Versailles and Vnukovo was one of its finest grottoes,

though the whereabouts of several other retreats that fitted this

description was better known to the general public. Peredelkino, just

two bucolic whistlestops away on our railway line, had recently buried

Boris Pasternak. We still used his septic tank man. He arrived every

spring to pump our sewage into his cistern, his literary loyalties evenly

divided among his customers. He admired our late neighbour, the

poet with the pen name meaning Crimson who once wrote a song

called 'Broad is My Native Land'. It was the logical equivalent of

'America the Beautiful', but much more famous:

Broad is my native land,

With forests, rivcrs, fields aplcnry.

Crimson himself was roughly as famous as Walt Disney, and the

architectural follies of his house, whose peaked orange roof would be

visible from our terrace after the leaves fell in autumn, reflected

something of his analogue's distant world. Each house stood on its

own land, usually ten or fifteen acres, surrounded by a picket fence

that was painted green if the original owner was still alive, or weather-

beaten and with long splinters if he was dead. Crimson's, where it

connected with ours forming a kind of narrow wedge, had crumbled

out altogether, and there you could crawl through to his thicket of

raspberry bushes, peacefully going wild in the totalitarian gloom. To

get to the opening you passed under the apple trees of our orchard,

sixty-five in all. We also had three pear trees, and a thicket of

gooseberries and currants to rival his raspberries. But it was what lay

to the side that made our house the grandest in Vnukovo. To the side

lay a birch grove, vestals in white improbably edged in black Catalan

lace, running away from the eye every time it blinked to stop them.

At the end of the grove was another fence and another dead owner, a

novelist by the name of Cymbal. That is what the name meant,

anyway. Cymbal's famous novel was called The White Birch, and sharp

tongues would recite a limerick whose hero progressed from the white

birch of Vnukovo to the white silverfoil top of the vodka bottle to the

white heat of delirium tremens and finally to White Posts, a mental

hospital of distinction not far from Moscow. Be that as it may,

Cymbal's neglected property had nothing to olfer. The birch grove

receded just before it reached his fence, and even the mushrooms

seemed to disappear as you approached the fence from our side. The

best places to find them in the grove were along the fence which

OUT OF PARADISE

separated us from the composer who bore the name of the River

Danube, or else near the front fence, beyond which ran the road called

Mayakovsky Street. Ours was No. 4, Cymbal's was No. 6. Across the

road, at No. 3, was the house of another writer, also very famous,

although nobody remembered why. No. 5, down the street, was owned

by a poet whose name would be Marmot in English translation- His

wartime lyric, about fire beating in the stove, was not quite as famous

as 'Broad is My Native Land', but songs, after all, are supposed to be

more popular than poems:

Fire beats in the narrow stove,

And the resin is likc a tcar.

Perhaps I simplify. Still, Marmot's poems were not meant to be

di{Ecult. Further down at No. 7, on the assumption of relative equality

among the muses, lived the founder of the puppet theatre, a Diaghilev

of the inanimate. It was said that he kept pet alligators, but to what

extent this was true is now hard to say since we never visited our

neighbours. Except our immediate neighbours, both women. One

lived at No. 2 with her husband, a film director. She was Vnukovo's

movie star, and as the country's film industry was never very prolific

even in the good old days, it followed that she had to combine the

beauty of Marilyn Monroe and the intellect of Katharine Hepburn

with all the permutations of charm and sophistication imaginable in

between. Her Christian name was Love, of course, and the surname

can be rendered as Eagle. Together with Danube, Crimson and the

original owner of our own No. 4, a Frank Sinatra figure who may be

recalled as Cliff, Miss Eagle and her husband had made the film

industry what it was. Their happiest collaboration, indeed a master-

piece of optimism, was called Joll2 Fcllows. It accounted for roughly

one-third of all famous comedies ever produced, the other two also

starring Miss Eagle and directed by her husband, who started his

career with Eisenstein on the Battlcship Potemkin and was later

entrusted with such sensitive subjects as Encountcr on tlu Elbc. The

other woman we visited lived at No. l. She was a distant relation of

the original owner, a scientist who discovered the secret of immortal-

ity. This secret was of great interest to the ruler of a vast and powerful

country like ours, and he showered her with honours until his death

from cerebral haemorrhage. Sharp tongues later explained that,

simply put, the scientist's secret was a highly diluted solution of

caustic soda in which you bathed regularly. But as she too had now

THE GINGERBREAD RACE

died, of old age or a broken heart or some other cause embarrassingly

unbecoming a person of such uncompromisingly scientific outlook,

only the rumours of people with severe burns caused by their pursuit

of immortality still circulated, while the older rumours, the glorious

old rumours of her incontrovertible successes, had apparently died

with her. Zina, who inherited the villa that was once a personal gift

from the ruler, must have thought the whole thing terribly unfair

because she was kind and kind people think most things terribly

unfair. In a way it was, but we never discussed the matter. Zina had

sixteen cats and, bless her kind heart, looked like one, although it was

difficult to decide which one. It varied from day to day. The animals,

as she called them, were all deformed and quiet, and since I already

knew Dostoevsky's novel it was impossible not to think of them as the

insulted and injured of the title. Zina was the only truly obscure

inhabitant of Vnukovo, and the only one who was poor. For the

animals she cooked a kind of nightmare stew, although at times it

resembled plain gruel, perhaps simply oatmeal porridge with lots of

innocent water, which was sticky and therefore frightening to a child

who had never been exposed to life in the raw. She served the gruel at

dusk, on the front porch of the crumbling house , with a heart-rending

cry of 'Animals!' And, from the four corners of the garden, the animals

would leap, hobble, or crawl, depending on the nature and extent of

the injuries they had sustained in their formative years, meekly and

noiselessly. In the evenings she watched television with her husband,

a tired older man who, like her, never did or said a cruel thing in his

life. What bile Kolya had in him he reserved for the television. If a

singer sang, he would laugh demonically and exclaim: 'Is this singing?'

If the news came on, he would snort: 'Is this news?' The only

exception was what he called modern art, which he loathed despite

the fact that it never appeared on the screen. To compensate, he had

a reproduction of the Picasso etching of Don Quixote tacked, upside-

down, to the wall above the television set, presumably in order to say

'Is this art?', or even 'Is this Don Quixote?', and to enjoy its

humiliation when nothing on the screen diverted his selectively

jaundiced eye. Their garden had very late apples, which lasted even

longer into the winter than our own Antonov variety, and as we

munched them Kolya would occasionally hurl a core at the etching,

making even more of a mess of Don Quixote, he explained, than the

artist had. From their gate to ours was a few hundred yards, but at

midnight in winter it seemed much farther. During the day, in