Table Of Content8.

om

0 1 8

•

I n6

~~ by~·"

Botty .

Frio dan

"THE BOOK WE WERE WAITING FOR . . . THE

WISEST, SANEST, SOUNDEST, MOST UNDERSTAND·

ING AND COMPASSIONATE TREATMENT OF AMERI·

CAN WOMAN'S GREATEST PROBLEM."

-Ashley Montagu

"This is one of those rare books we are

endowed with only once in several decades;

a volume which launches a major social

movement, toward a more humane and

just society. Betty Friedan is a liberator of

women and men."

-Amitai Etzioni,

Chairman, Department of Sociology,

Columbia University

"The most important book of the twentieth

century . . . Betty Friedan is to women

what Martin Luther King was to blacks."

-Barbara Seaman, author of Free and Female

"It states the trouble with women so clearly

that every woman can recognize herself.

. . . Things are different between men and

women because we now have words for the

trouble. Betty gave them to us."

-Caroline Bird, author of

Everything a Woman Needs to Know

to Get Paid What She's Worth

o .

'Fomlnino ,

~tiquo

.. ..

~· ~~by~~·

Botty

~

Friodan

With aNew Introduction and Epilogue

by the Author

A DELL BOOK

I:

1'

Published by

~. DELL PUBLISHING CO., INC.

1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza

New York, New York 10017

t

Copyright © 1974, 1963 by Betty Friedan

Selections from this book have appeared in

Mademoiselle © 1962 by the Conde Nast Publications, Inc.,

Ladies' Home Journal © 1963 by Betty Friedan and

McCall's © 1963 by Betty Friedan.

Introduction and Epilogue first published in the

New York Times Magazine. Copyright © 1973 by

Betty Friedan.

All rights reserved. For information contact

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

New York, New York 10003

Dell ® TM 681510, Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

IBSN: 0-440-12498-0

Reprinted by arrangement with

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

Previous Dell Edition #2498

New Dell Edition

First printing-September 1977

Second printing-June 1979

I

I

For all the new women,

and the new men

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION 1

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 7

ONE

THE PROBLEM THAT HAS NO NAME 11

TWO

THE HAPPY HOUSEWIFE HEROINE 28

THREE

THE CRISIS IN WOMAN'S IDENTITY 62

FOUR

THE PASSIONATE JOURNEY 73

F I V E

THE SEXUAL SOLIPSISM

OF SIGMUND FREUD 95

SIX

THE FUNCTIONAL FREEZE,

THE FEMININE PROTEST,

AND MARGARET MEAD 117

SEVEN

THE SEX-DIRECTED EDUCATORS 142"

I,

,

EI GHT

THE MISTAKEN CHOICE 174

N I N E

THE SEXUAL SELL 191

f TEN

HOUSEWIFERY EXPANDS TO

!

FILL THE TIME AVAILABLE 224

ELEVEN

THE SEX-SEEKERS 241

TWELVE

PROGRESSIVE DEHUMANIZATION:

THE COMFORTABLE CONCENTRATION CAMP 271

THIRTEEN

THE FORFEITED SELF 299

FOURTEEN

A NEW LIFE PLAN FOR WOMEN 326

EPILOGUE 365

NOTES 381

INDEX 409

INTRODUCTION

JO THE TENTH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

IT IS A DECADE NOW SINCE THE PUBLICATION OF

The Feminine Mystique, and until I started writing the

book, I wasn't even conscious of the woman problem.

Locked as we all were then in that mystique, which kept

us passive and apart, and kept us from seeing our real

problems and possibilities, I, like other women, thought

there was something wrong with me because I didn't have

an orgasm waxing the kitchen floor. I was a freak, writing

that book-not that I waxed any floor, I must admit, in

the throes of finishing it in 1963.

Each of us thou ht she was a freak ten ears a 0 if she

didn't expenence~~~ ~~ious or~ashc ment the

Commercials prom;;;ed 3i/h;;; waxing the kitchen floor.

""HOWever much we enjoyed being Junior's and Janey"S or~

Emily's mother, or B.J.'s wife, if we still had amibitions,

ideas about ourselves as people in our own right-well,

we were simply freaks, neurotics, and we confessed our

sin or neurosis to priest or psychoanalyst, and tried hard

to adjust. We didn't admit it to each other if we felt there

should be more In hfe {han eanut-butter sandWIches WIth

e kids, throwing power In 0 was ng mac ine

didn't make us relive our wedding night, if getting the

socks or shirts pure white was not exactly a peak experi

ence, even if we did feel guilty about the tattletale gray.

Some of us (in 1963, nearly half of all women in the

me

United States) Were already commIftmg UnpardObable

SIn of working outside the home to belp pay the mortgage

"or W'0cery tid!. Those who did felt guilty, too-about be

~mg their femimmty, yndermining their husbands' mas

culImty, and neglecting their children by daring to work

for money at all, no matter how much it was needed.

They couldn't admit, even to themselves; that the:ll-resent

t:..d being paid half what a man would have been paid for

2 THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

the job, or always being passed over for promotion, or

writing the paper for which he got the degree and the

raise.

A suburban neighbor of mine named Gertie was having

coffee with me when the census taker came as I was writ

ing The Feminine Mystique. "Occupation?" the census

taker asked, "Housewife," I said. Gertie, who had cheered

me on in my efforts at writing and seIling magazine arti

cles, shook her head sadly. "You should take yourself

more seriously," she said. I hesitated, and then said to the

census taker, "Actually, I'm a writer." But, of course, I

then was, and still am, like all married women in Amer

ica, no matter what else we do between 9 and 5, a house

wife. Of co se single women di 't "house-

. ". the cens e came around ut even ere,

society was less interested in what these women were

~persons in the world than in askmg, "WhY lsn~

'IiiCegiIi like you married.:E And so they: too, were~

~ged to take themselves seriously.

It seems such a precarious accident that I ever wrote

the book at all-but, in another way, my whole life had

prepared me to write that book. All the pieces finally

came together. In 1957, getting strangely bored with writ

ing articles about breast feeding and the like for Redbook

and the Ladies' Home Journal, I put an unconscionable

amount of time into a questionnaire for my fellow Smith

graduates of the class of 1942, thinking I was going

. ove the current notion that education had fitted us ill

for our ro e as women. But t e questionnaire raised more

questions than it answered for me-education had not ex

actly geared us to the role women he~ng tQ..PW. it

seemed. The suspicion arose as to weer it was the edu

cation or the role 'that was wrong. McCall's commissioned

an article based on my Smith alumnae questionnaire, but

the then male publisher of McCall's, during that great era

of togetherness, turned the piece down in horror, despite

underground efforts of female editors. The male McCall's

editors said it couldn't be true.

I was next commissioned to do the article for Ladies'

Home Journal. That time I took it back, because they

rewrote it to say just the opposite of what, in fact, I was

trying to say. I tried it again for Redbook. Each time I

was interviewing more women, psychologists, sociologists,

INTRODUCTION 3

marriage counselors, and the like and getting more and

-more sure I was on the track of something. But what? I

needed a name for whatever it was that kept us from

using our rights, that made us feel guilty about anything

we did not as our husbands' wives, our children's mothers,

but as people ourselves. I needed a name to describe that

guilt. uolike tbe guilt women used to feel about sexual

needs, the guilt they felt now was about needs . ,

t e sexua e 1 on 0 women, the mystique of femi

nine fulfillment-the femmme mystique.

"The editor of Redbook told my agent, "Betty has gone

off her rocker. She has always done a good job for us, but

this time only the most neurotic housewife could

identify." I opened my agent's letter on the subway as I

was taking the kids to the pediatrician. I got off the sub

way to call my agent and told her, "I'll have to write a

book to get this into print." What I Was writing threat

ened the very foundations of the women's magazIne

World-the feminine mystique.

When Norton contracted for the book, I thought it

would take a year to finish it; it took five. I wouldn't have

even started it if the New York Public Library had not, at

just the right time, opened the Frederick Lewis Allen

Room, where writers working on a book could get a desk,

six months at a time, rent free. I got a baby-sitter three

days a week and took the bus from Rockland County to

the city and somehow managed to prolong the six months

to two years in the Allen Room, enduring much joking

from other writers at lunch when it came out that I was

writing a book about women. Then, somehow, the book

took me over, obsessed me, wanted to write itself, and I

took my papers home and wrote on the dining-room table,

the living-room couch, on a neighbor's dock on the river,

and kept on writing it in my mind when I stopped to take

the kids somewhere or make dinner, and went back to it

after they were in bed.

I have never experienced anything as powerful, truly

mystical, as the forces that seemed to take me over when

I was writing The Feminine Mystique. The book came

from somewhere deep within me and all my experience

came together in it: my mother's discontent, my own

training in Gestalt and Freudian psychology, the fellow

ship I felt guilty about giving up, the stint as a reporter

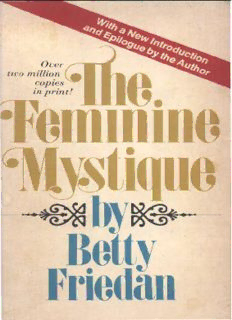

Description:Landmark, groundbreaking, classic — these adjectives barely describe the earthshaking and long-lasting effects of Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique. This is the book that defined "the problem that has no name," that launched the Second Wave of the feminist movement, and has been awakening wome