Table Of Contentthe dozens

This page intentionally left blank

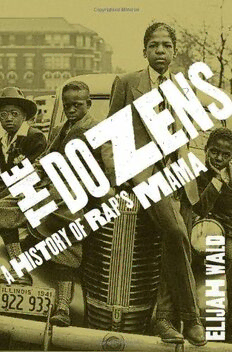

elijah wald

THE DOZENS

A History of Rap’s Mama

1

1

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford University’s objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offi ces in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright © 2012 by Elijah Wald

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wald, Elijah.

The dozens : a history of rap’s mama / Elijah Wald.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-989540-3

1. African American wit and humor. 2. Invective—Humor. 3. Dozens (Game) 4. African Americans—Social

life and customs. 5. Rap (Music) 6. African Americans—Music. I. Title.

PN6231.N5.W35 2012

398.708996073—dc23 2011043649

“Horn of Plenty” from THE COLLECTED POEMS OF LANGSTON HUGHES by Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold

Rampersad with David Roessel, Associate Editor, copyright © 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. Used by permission of

Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.

“The Thirteens (Black),” “The Thirteens (White),” from JUST GIVE ME A COOL DRINK OF WATER ’FORE I DIIIE by

Maya Angelou, copyright © 1971 by Maya Angelou. Used by permission of Random House, Inc.

Keep It Clean. By Charley Jordan. Copyright © 1930 UNIVERSAL MUSIC CORP. Copyright Renewed. All Rights Reserved

Used by Permission. Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard Corporation.

Dirty Nursery Rhymes. Words and Music by Luther Campbell, David Hobbs, Mark Ross, and Christopher Wong Won.

Copyright © 1989 Music Of Ever Hip-Hop (BMI). Worldwide Rights for Music Of Ever Hip-Hop Administered by BMG

Chrysalis. International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard Corporation.

The Dirty Dozens. Words and Music by J. Mayo Williams and Rufus Perryman. Copyright © 1929, 1930 UNIVERSAL

MUSIC CORP. Copyright Renewed. All Rights Reserved Used by Permission

Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard Corporation.

Old Jim Canaan’s. Words and Music by Robert Wilkins. Copyright © 1985 Wynwood Music Co., Inc.

Used by permission of Wynwood Music Co., Inc.

Quotations from Rudy Ray Moore’s performances of “Signifying Monkey” and “More Dirty Dozens” courtesy of Donald H.

Randell/Dolemite Records, w ww.dolemiterecords.com.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

Contents

Preface and Acknowledgments vii

A Half-Dozen Defi nitions x

one A Trip down Twelfth Street 3

two The Name of the Game 19

three Singing the Dozens 31

four Country Dozens and Dirty Blues 43

fi ve The Literary Dozens 63

six Studying the Street 79

seven The Martial Art of Rhyming 101

eight Around the World with Your Mother 121

nine African Roots 135

ten Slipping Across the Color Line 153

eleven Why Do They (We) Do That? 169

t welve Rapping, Snapping, and Battling 183

Notes 201

Selected Bibliography 227

Index 233

This page intentionally left blank

Preface and Acknowledgments

This project began more or less by accident. I was exploring connec-

tions between blues and hip-hop, wanted to learn more about the

dozens, and could not fi nd a book on the subject. So I began poking

around, and the more I found the more fascinated I became. The result

is a broad survey of songs, memoirs, fi ction, journalism, academic

research, anecdotes, and other material that intrigued or amused me,

and an attempt to provide a sense of the dozens’ role in American cul-

ture and its relationship to other traditions around the world. I have

drawn on a wide range of previous writings, recordings, and scholar-

ship, and must start by acknowledging my debt to the myriad artists

and researchers who made these explorations possible.

Before making more specifi c acknowledgments, I should add a

brief note about language. The dozens is intentionally offensive and

outrageous, so it would be absurd to censor this material or apologize

for it, but I nonetheless had to make some choices about presentation.

When transcribing recorded material, I tried to respect the syntax and

grammar of the speakers and singers but not to convey their pronunci-

ations, except in situations where it was necessary for a rhyme or pun.

However, when quoting the transcriptions of other writers I left their

spellings intact. In many cases this was a matter of respecting my more

knowledgeable predecessors, but even when I consider the rendering

of the dialect inept or racist it may be historically signifi cant or help

readers assess the biases or viewpoints of the writers.

I followed similar rules for translations from languages other than

English. Many translators used euphemisms or academic terminology

in the place of words and phrases they considered obscene or impolite,

and I let those choices stand. But in my own translations I have tried to

use words that parallel the original usage, translating the Spanish

chinga and French-Arabic n ique as “fuck” rather than “have sexual

intercourse” and coño and c on as “cunt” rather than “vulva” or “vagina.”

Any faithful translation must attempt to convey emotional and societal

shadings as well as the dictionary defi nitions of words, and this is par-

ticularly true of obscenities, since their literal meanings are often mis-

leading. As Lenny Bruce explained, a Yiddish-English dictionary may

defi ne schmuck as “penis,” but that is not how it is used. He gave the

example of someone saying, “We went on a trip and who do you think

did all the driving? Me, like a schmuck . . .” then provided the analysis,

“‘Me like a schmuck’ isn’t dirty unless you’re a faggot Indian: ‘ How ,

white man. Me like-a schmuck.’” 1

Some readers may fi nd Bruce’s explanation more offensive than the

word he was defending, which is in part why I present it. Many people

who have no problem with dirty words are nonetheless troubled by the

sexism, homophobia, or racism connected to their use, whether by

“folk” informants, by academics, by entertainers, or by me. So I wel-

come criticism and discussion of my choices—I wrote this book to

open a conversation, and look forward to seeing what sequelae ensue.

As to specifi c acknowledgments, I must fi rst thank Roger Abra-

hams, whose pioneering work on the dozens and analogous traditions

in the diaspora and on pre-twentieth-century African American cul-

ture laid the foundation for all future research in this fi eld, and who

compounded my debt by cordially answering my phone calls and

emails. Special thanks are also due to Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff

for giving me access to their fi le of early dozens-related clippings, and

William Ferris for permission to quote his unpublished research from

Mississippi.

One of the pleasures of researching this book was the graciousness

and generosity with which other researchers shared their knowledge.

Among the many people who provided clues, answers, advice, or mate-

rial, sometimes with commendable brevity and sometimes in impressive

depth, are Gaye Adegbalola, John Anderson, Ken Bilby, Margaret Brady,

Simon Bronner, Elaine Chaika, Paul Chevigny, David S. Cohen, Ed

Cray, Morgan Dalphinis, Daryl Cumber Dance, Robert Forbes, Paul

Garon, Edgar Gregersen, Ian Hancock, Veronique Hélénon, Jack Horn-

tip, Bruce Jackson, Bob Koester, Jack Landrón, Jooyoung Lee, Suzan-

nah Maclay, David Mangurian, Elizabeth McAlister, Alejandro Mejía

Abad, Ali Colleen Neff, Edward Powe, Azizi Powell, Ann and Steve

viii Preface and Acknowledgments

Rabson, Lee Rainwater, Howard Rye, Mona Lisa Saloy, Chris Smith,

Geneva Smitherman, Ned Sublette, Stefan Wirz, and Karl Gert zur

Heide. I am sure there were others, and beg forgiveness of anyone whose

name was omitted through my carelessness. Rusti Pendleton deserves a

special shout-out for making me welcome at the rap contests he held at

the Dublin House in Dorchester, introducing me to a world of which I

was woefully ignorant. And Ian B. Walters mercilessly demonstrated the

dozens to me and provided lines that I will undoubtedly steal.

I owe a special debt to the writers, performers, and researchers who

preceded me; Paul Oliver for his superbly researched chapter on the

dozens in blues and so much other work over the years, Zora Neale

Hurston, William Labov, Thomas Kochman, Onwuchekwa Jemie,

and so many others whose names are too numerous to cite but whose

contributions will be obvious to any reader. Further thanks are due to

the staffs of the Southern Folklore Archive at the University of North

Carolina, the John Hay Library at Brown University, the UCLA Music

Library and Ethnomusicology Archive, the Tufts and Harvard Uni-

versity libraries, and all the other people who attempted to answer my

crazy questions. Likewise to everyone on the pre- and postwar blues

internet lists, the jazz research list, and various other internet forums

that permitted me to post potentially offensive queries.

For advice and encouragement, infi nite thanks are due to my wife,

Sandrine Sheon, who was enthusiastically supportive and startled some

friends by repeating favorite insults—as well as donating her design

expertise, providing advice on the cover, and laying out the photo

insert. To my agent, Sarah Lazin, whose comments on an early draft

greatly improved the later drafts. For giving this project a home and

steering it to completion, I thank my editor, Suzanne Ryan—it is all

too rare these days to get an editor who takes the time and trouble to

really edit, and I know how lucky I am. And those thanks should extend

to everyone at Oxford University Press, notably including my copy

editor, Ben Sadock, a credit to his métier.

Preface and Acknowledgments ix