Table Of ContentS ustainab le H ousing

Reconstruction

Through (cid:400)(cid:401) case studies from (cid:3)ustralia, (cid:6)angladesh, (cid:15)aiti, Sri Lanka,

the (cid:38)S(cid:3) and (cid:40)ietnam, Sustainable Housing Reconstruction f ocuses on

the housing reconstruction process after an earthquake, a tsunami, a

cyclone, a (cid:89)ood or a fire. (cid:9)esign of post-disaster housing is not simply

replacing the destroyed house but, as these case studies highlight,

a means not only to build a safer house but also a more resilient

community(cid:312) not to simply return to the same condition as before the

disaster, but an opportunity to build back be(cid:130)er.

T h e b ook ex p lores tw o main th emes:

(cid:334) Housing reconstruction is most successful when involving the users in the

design and construction process.

(cid:334) Housing reconstruction is most effective when it is integrated with community

infrastructure, services and the means to create real livelihoods.

The case studies included in this book highlight work completed by different

agencies and built environment professionals in diverse disaster-affected

contexts. With a global acceleration of natural disasters, often linked to

accelerating climate change, there is a critical demand for robust housing

solutions for vulnerable communities.

This book provides professionals, policy-makers and community stakeholders

working in the international development and disaster risk management sectors,

with an evidence-based exploration of how to add real value through the design

process in housing reconstruction. Herein then, the knowledge we need to build,

an approach to improve our processes, a window to understanding the complex

domain of post-disaster housing reconstruction.

es t h e r ch a r le s w o r t h is Associate Professor and the Director of the Humanitarian

Architecture Research Bureau (HARB) in the School of Architecture and

Design, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. Esther is the Founding Director

of Architects Without Frontiers (AWF). Her most recent book, H umanitarian

Architecture: 15 Stories of Architects Working after Disaster, was published by

Routledge in 2014.

i(cid:91)ekhar ahmed is a Research Fellow in the Humanitarian Architecture Research

Bureau (HARB), School of Architecture and Design, RMIT University, Melbourne,

Australia. His research interests span the areas of disaster risk reduction, climate

change adaptation, urbanisation and community development.

Far too many disaster reconstruction projects regard

the efficient delivery of rows of faceless houses as

the measure of success. However, in this vital study

Esther Charlesworth and Iftekhar Ahmed move well

beyond this notion. They claim, in twelve well-chosen

international case studies, that housing reconstruction

can be sustainable, delivering ‘added-value’. This can

include newly acquired building skills that strengthen

livelihoods, safety from hazard forces, community

resilience and a close identification of users with their

creation. The book is a joy to read, aided by a splendid

layout and deligh(cid:127)ul illustrations and must qualify

as the best looking book on disaster recovery ever

p ubli shed!

Ian Davis, Visiting Professor in Disaster Risk

Management in Copenhagen, Lund, Kyoto and Oxford

Brookes Universities

The daunting task of rebuilding after disaster requires

strong inclusion of affected people and governments,

and after decades of such programmes, Esther

Charlesworth and Iftekhar Ahmed have added

significantly to the debate with Sustainable H ousing

Reconstruction. This detailed and colourful book is

essential reading for those involved, covering a range of

disasters, typologies and program approaches, pu(cid:2478)ng

the interests of affected people at the centre of the

debate.

Brett Moore, Global Shelter, Infrastructure and

Reconstruction Advisor, World Vision International

Post-disaster politicians always say, ‘We shall

rebuild here now’. What rubbish. The disaster struck

accidentally but the damage is no accident. Damaged

buildings and housing are the result of hastily and

poorly built structures that could not sustain the

forces of nature. So, rebuilding has to be carefully

tho ugh t out and w ell ex ecuted so ther e is not a rep eat

of the catastrophe that occurred. Sustainable H ousing

Reconstruction is a timely antidote to the rush to rebuild

by laying out with cases how human and physical

repair has to occur for the reconstructed post-disaster

community to be fit for the future.

Edward J. Blakely, Honorary Professor of Urban Policy,

United States Studies Centre at the University of

Sydney and Director of Recovery post-Katrina for the

City of New Orleans 2007–2009

S ustainab le H ousing

Reconstruction

D esigning resilient housing

a(cid:91)er natural disasters

es t h e r ch a r l e s w o r t h and i(cid:91)ekhar ahmed

First published 2015

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor (cid:349) Francis Group, an

informa business

(cid:353) 2015 Esther Charlesworth and Iftekhar Ahmed

The right of Esther Charlesworth and Iftekhar Ahmed to

be identified as authors of this work has been asserted

by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be

reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by

any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known

or hereafter invented, including photocopying and

recording, or in any information storage or retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the

publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be

trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only

for identification and explanation without intent to

infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Charlesworth, Esther Ruth, author.

Sustainable housing reconstruction: designing resilient

housing after natural disasters / Esther Charlesworth

and Iftekhar Ahmed.

p ages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Disaster victims--Housing--Case studies.

2. Ecological houses--Case studies. 3. Buildings--Repair

and reconstruction--Case studies. 4. Disasters--Social

aspects--Case studies. I. Ahmed, Iftekhar, 1962- author.

II. Title.

HV554.5.C43 2015

363.5’83--dc23

2014034933

ISBN: 978-0-415-70260-7 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-415-70261-4 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-73541-2 (ebk)

Typeset in Lato

Book design, layout and typese(cid:2478)ng by HD Design

Original Book design concept by Adrian Marshall

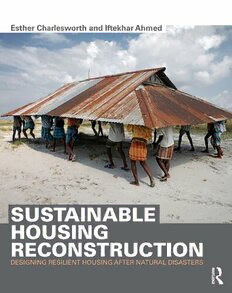

Cover photo by Jonas Bendiksen

C ontents

Figures vi

Foreword: Learning from the Shelter Sector viii

GRAHAM SAUNDERS

Acknowledgements x i

introduction: More than a roof overhead: post-disaster x ii

housing reconstruction to ena(cid:48)le resilient communities

part i xiv

overview: achievements in housing reconstruction

despite mounting odds

part ii 2

the case studies

bush(cid:67)re (cid:327) australia 4

Black Saturday bushfires, 2009 7

Linking temporary and permanent housing: Kinglake

Black Saturday bushfires, 2009 1 7

Linking temporary and permanent housing: Marysville

Cyclone (cid:327) bangladesh 26

Cyclone Aila, 2009 29

Owner-driven reconstruction

Cyclone Aila, 2009 37

Community-based reconstruction

earth(cid:116)uake (cid:327) haiti 48

Earth(cid:116)uake, 2010 51

Community redevelopment program

Earth(cid:116)uake, 2010 59

Integrated neighbourhood approach

tsunami (cid:327) sri lanka 68

Indian Ocean tsunami, 2004 7 1

Community resettlement

Indian Ocean tsunami, 2004 79

Owner-driven reconstruction

hurricane (cid:327) usa 88

Hurricane Katrina, 2005 91

Consultative housing reconstruction

Hurricane Katrina, 2005 99

Musicians’ Village

typhoon (cid:327) Vietnam 108

Typhoon Xangsane, 2006

Typhoon Ketsana, 2009 1 1 1

Housing reconstruction and public awareness

Typhoon Xangsane, 2006 119

Child-centred housing reconstruction

P a r t iii 128

Conclusion: lessons from the case studies

Bibliography 134

Index 136

(cid:1354)

F igures Terry and Sharon; their house; and the floor plan of their

house. 22

Norman Fiske. 23

Foreword Cyclone (cid:325) Bangladesh

Meeting local needs: An IFRC-supported community overview

rain water tank in Bangladesh. ix At risk: The Khulna District shoreline, typical of

Technical advice: IFRC supervision helps to ensure Bangladesh’s highly vulnerable coast. 26

appropriate housing reconstruction in Haiti. x Stabilised: A UNDP-built house on an earthen plinth

stabilised with cement. 29

Introduction

owner-driven reconstruction

Safer: Post-disaster housing in Vietnam ‘built back better’ Map of Bangladesh showing the location of

than before. xiii Khulna District and Dacope Sub-district. 29

Teamwork: Many people’s skills contribute to a house being Low-lying: Dacope and its coastal environment. 31

rebuilt in Marysville after the Black Saturday bushfires. xiii Clean: A newly built community pond sand filter. 32

Built for all: The community latrine and bathroom building. 33

Part I Overview

Multiple benefits: Roads built through the cash-for-work

program serve as dykes. 33

Range of stakeholders: Even children contribute to the

Safe from floods: This school playground was raised above

reconstruction task in Bangladesh. xiv

flood level through the cash-for-work program. 33

Complex tasks: Rebuilding after a massive earthquake

Moyna; her house; and floor plan. 34

in Haiti. 1

Yusuf; his house; and its floor plan. 35

Part II The case studies

Community-(cid:48)ased reconstruction

Aquaculture: A view from Shyamnagar showing its

Bushfire (cid:325) Australia

low-lying environment and large fish-farming ponds. 37

overview Map of Bangladesh showing location of Satkhira. 37

Aftermath: Marysville soon after the bushfire. 4 Water for many needs: Ponds in front of each house

Architects’ contribution: Narbethong Community Hall. 7 provide fish and are used for bathing and washing. 39

High and dry: By piling earth from pond excavations, the

kinglake

settlement is raised to protect it from high water. 40

Map of Victoria Australia showing location of Kinglake. 7

Model approach: The design workshop with community

Forested: Kinglake and the hills of the Kinglake Range. 9

members at BRAC University. 41

Student-led: The community barbeque pavilion in the

Saleha; her house; and its floor plan. 42

temporary village, designed and built by Monash

Anisur; and his house. 43

University Architecture students. 11

Primary: The school is a key community facility. 45

Central: The children’s playground set at the heart of the

Kinglake temporary village. 11 Earth(cid:116)uake (cid:325) Haiti

Well-sited: Aerial view and site plan of the Kinglake

temporary village. 12 overview

Jacqueline Marchant; the Re-Growth Pod being craned Vulnerable: Informal settlements such as this are

in; installed; and after five years; and Design drawings widespread in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. 48

for the Re-Growth Pod. 14 Relocation: A newly built settlement at Zoranje, north of

Greg Rogers; a floor plan of a two-bedroom cottage at Port-au-Prince. 51

the temporary village. 15 Villa rosa

Map of Haiti showing the location of Port-au-Prince. 51

Marysville

Destruction: A resident at the remains of his house. 17 Poor-quality: A view of Villa Rosa. 53

Map of Australia showing location of Marysville. 17 Infrastructure: Walkways, drainage and streetlights built

Future promise: Temporary village housing (later used as by AFH. 54

school camp buildings). 19 Tesie; and his house. 55

Trees retained: Site plan of the Marysville temporary village. 20 Clerge. His house is the red one beside the basketball court. 55

Innovations: The tools library (right) and belongings storage Mutilus; her house; and its floor plan. 56

shed (left) were important community facilities in the Venite; her house; and its floor plan. 57

Marysville temporary village. 21 integrated neigh(cid:48)ourhood approach

Room for all: The community dining hall in the temporary On the hill: A view from Delmas 30. 59

village (now used in the school camp). 21 Infrastructure: Paved walkway with drainage in Delmas 30. 61

vi

Figures

Solar: Street lights in Delmas 30 use solar power. 62 Musicians(cid:317) Village

Well-built: Stone retaining wall in Delmas 30. 63 Retaining heritage: the Musicians’ Village. 99

Marie; her house; and its floor plan. 64 Map of the Gulf Coast showing location of New Orleans. 99

Viergemene; and her house. 65 Not only houses: The support activities undertaken by

NOAHH are broad ranging and include running this

Tsunami (cid:325) Sri Lanka

shrift shop 101

Special care: Front view of duplexes for the elderly. 103

overview

Key: The Ellis Marsalis Center for Music. 103

An island country: Sri Lanka has extensive coastal

Play this: The children’s park in the Musicians’ Village. 103

communities. 68

Multiple components: Site plan of Musician’s Village. 103

Inland: Donor-driven housing in Hambantota New Town,

Smokey; his house; and its floor plan. 104

one of the largest post-tsunami resettlement projects in

Alvin; and his house. 105

Sri Lanka. 71

Rhonda; and her house. 105

Community rese(cid:130)lement

Map of Sri Lanka showing location of Seenigama. 71 Typhoon (cid:325) Vietnam

On the Indian Ocean: A view from Seenigama showing its

overview

coastal environment. 73

Disaster-prone: A view from coastal Hue, Vietnam. 108

Well-planned: A view from Victoria Gardens showing

Safe-refuge: A house built in the government’s ‘716

community facilities. 75

Program’. 110

A good place for living: Site Plan of Victoria Gardens. 75

Shantha, his house and its floor plan. 76 housing reconstruction and pu(cid:48)lic awareness

Sureka; and her house. 77 Coastal wetlands: A view from a typhoon ravaged area

Gamini; and his house. 77 in Hue. 111

Himali; and her house. 78 Map of Vietnam showing location of Hue. 111

In the community: The FOG centre. 78 Unsafe: Houses such as this in Hue are vulnerable to

disasters. 113

owner-driven reconstruction

Yen; her house; and its floor plan. 116

Lakeside: A view from Tissa showing its rural environment. 79

Dung; and his house. 117

Map of Sri Lanka showing location of Tissamaharama. 79

Cu; and his house. 117

Typical: A mud house in Tissa. 81

Talking through issues: Consultation with beneficiaries

Owner’s choice: Houses of diverse forms and appearances

was a key aspect of DWF’s work. 118

were built in Uddhakandara through the owner-driven

process. 83 Child-centred housing reconstruction

Building for the future: The community centre. 83 City on the water: Danang showing its coastal location. 119

Life-sustaining: Rainwater tanks were provided to all the Map of Vietnam showing location of Danang. 119

beneficiary households. 84 Verandah added: The SCUK houses had a provision for

Anura; and his house. 85 adding a front verandah, which most beneficiaries had

Nishanti; her house; and its floor plan. 85 built. 121

Rehabilitated: A pre-school in the SCUK project. 122

Hurricane (cid:325) USA

Anh; her house; and its floor plan. 123

Strength: Design drawing showing the three continuous

overview

reinforced concrete bands that contribute to the house’s

Exposed: Gulf Coast: Biloxi, Mississippi, hit hard by

typhoon-resistance. 124

Hurricane Katrina. 88

Dangerous buildings: Thin brick walls were common,

International architects: Houses built in the Make It Right

making houses vulnerable to typhoons. 124

project in the Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans. 91

Secured: Metal angles on the roof protect the roofing

Consultative housing reconstruction

sheets against strong wind. 125

Map of the Gulf Coast showing location of Biloxi. 91

Sub-tropical: The project is located in Biloxi’s coastal Part III: Conclusion

wetlands environment. 93

More than housing: Support for livelihoods makes

David; his house; and its floor plan. 95

housing reconstruction more effective. 128

Owner-detailed: A house with exterior colour of the

Urban challenge: Rebuilding a community takes more

beneficiary’s choice: note the timber sidings used instead

than good house design. 131

of vinyl. 96

Beneficial outcomes: Life after sustainable housing

Kept: Houses were designed to blend in with nature, such

construction in Seenigama 133

as with the oak trees that survived the hurricane. 96

(cid:1354)

Flora; her house; and its floor plan. 97

vii

(cid:13)ore(cid:137)ord housing, schools and infrastructure. Housing is a primary

human need, and is often a household’s most valuable asset.

Quantifying the scale of the humanitarian shelter sector

and the housing needs resulting from disasters and crises

Learning from the shelter

is a challenge. It is interesting to note that 75 per cent of

sector the disaster response activities of the 189 National Red

Cross and Red Crescent Societies (excluding health and food

Graham Saunders security emergencies) included the provision of housing

assistance to affected populations. The scale of need remains

head(cid:311) shelter and se(cid:130)lements

significant, as disasters in recent years have highlighted. The

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent extensive flooding in Asia in 2007 resulted in the homes of

Societies more than 60 million people being damaged or destroyed,

the 2010 floods in Pakistan destroyed 1.6 million homes,

Meeting shelter needs after natural disasters, military and over 1 million homes in the Philippines were damaged or

conflicts and other crises, through the provision of destroyed by the typhoon that struck in late 2013. Population

emergency shelter relief and longer-term reconstruction displacement as a result of conflict and civil unrest leads to

assistance, is not a new field of endeavour. The Red the need for both short- and longer term housing assistance,

Cross Red Crescent Movement archives reveal that in with over 2 million households displaced as a result of the

1889, after the South Fork Dam burst in Pennsylvania, crisis in Syria, 250,000 in the Central African Republic and

USA, the American Red Cross built six wooden, two- 100,000 in South Sudan in early 2014. However, the financial

storey buildings to temporarily house those whose and material resources to assist the households affected

homes had been damaged or destroyed by the flood by such disasters,from both the affected governments

waters. However, some would argue that the ‘business’ themselves and the international donors, can meet only some

of providing post-disaster housing has changed little of these needs.

since, highlighting the recent example of the large

For the majority of people, outside of a disaster or conflict,

numbers of wooden ‘sheds’ constructed to house those

ensuring adequate or appropriate housing is an iterative

rendered homeless by the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. In

process over time. The house may have been inherited,

2012 alone, some 32.4 million people were forced to

and adapted through repair or extension. Alternatively, the

leave their homes as a result of disasters, reflecting a

property or land may have been purchased, with a loan,

steady increase on preceding years. This new caseload

with cash, or through exchange, or constructed by the

of people requiring shelter or housing assistance is in

household themselves with their own labour or through the

addition to the 100 million slum dwellers whose lives

formal or informal engagement of others. Accommodation

were targeted for significant improvement by 2020 as

may be owned, or rented, may be substantially constructed

part of the Millennium Development Goals. How has

and durable or of simple construction to enable rapid

the approach to addressing housing and settlement

adaptation or relocation. Such processes are informed by

risks and vulnerabilities developed, and what have been

local housing typologies and building technologies, forms

the key lessons from what has been defined as the

of tenure for both land and property, social and familial

humanitarian shelter sector? These critical questions on

norms, and the economic and financial systems used by the

how to provide effective housing solutions are explored

respective community. In the recovery and reconstruction

through this innovative and timely book through looking

phase following a major disaster, typically when the scale

at housing reconstruction case studies in six countries.

of both national and international assistance decreases,

While every case study has presented its own unique

these processes are re-established over time as the affected

successes and challenges, Esther Charlesworth and

community strives to return to normality. However, in the

Iftekhar Ahmed have tried to identify what are the core

aftermath of disaster, particularly a rapid onset emergency

components of effective post-disaster housing; no easy

such as an earthquake, a hurricane, a landslide or sudden

task!

flooding, humanitarian shelter interventions typically ignore

The annual economic impact of disasters has been or inhibit such processes through external supply or product-

estimated by the United Nations as totalling US(cid:362)200 driven activities, such as the provision of tents or other forms

billion since the start of the twenty-first century, of prefabricated temporary housing. Although consideration is

resulting from the increasing frequency of smaller and often given to cultural concerns and the use of locally sourced

medium-scale disasters, increasing vulnerabilities through labour, such approaches typically do not fully capitalise on

urbanisation and social and economic marginalisation, existing housing processes. Perhaps of greater consequence

and the impacts of climate change. Following the Indian are the potential economic benefits that this book explores,

Ocean tsunami in 2004, it was estimated that nearly 50 such as investment in livelihood opportunities that could

per cent of the economic loss suffered by Indonesia was enable the affected community to recover from the disaster,

related to damage to the built environment, including

viii

Meeting loCal neeDs: (cid:3)n (cid:17)(cid:13)R(cid:7)-supported community rain water tank in (cid:6)angladesh.

and increased knowledge and understanding of the housing is to be done at both the programmatic level but crucially

and settlement risks that need to be addressed to reduce at the institutional level. Some of the case studies in this

the future vulnerability of both people and property. All the book, particularly from Haiti and Australia, show an emerging

examples in this book show how well-programmed post- recognition of the link between short- and long-term housing,

disaster reconstruction activities have economically benefited a pointer to dealing with this crucial challenge.

local businesses and construction workers, as well as building Key challenges for both strategic decision-makers and

local capacity and reducing disaster risk through building practitioners in addressing post-disaster housing needs

resilient housing. include defining the most appropriate interventions

The provision of rapid emergency housing assistance has addressing the risks and vulnerabilities, and understanding

significantly improved over the last decade, through improved the technical and regulatory environment to ensure the rapid

coordination, the advances in the quality and consistency of and equitable provision of assistance. Government ministries

shelter relief items, including plastic sheeting and tents, and and local authority offices often do include personnel

the provision of standardised housing kits, tools, materials and with relevant backgrounds in the built environment, but in

cash to enable self-recovery by affected households. There these times of lean central government and an increasing

is also far greater recognition of the need to identify and reliance on the contracting-in of expertise and capacity

address key housing and settlement risks and vulnerabilities when required, the in-house specialist know-how is not

from the outset of a response, through informed relief necessarily readily available. Similarly, many humanitarian

interventions and the inclusion of awareness-raising activities sh elter agencies lack dedicated sp ecialists w h o can address

or training as part of the on going programming. However, these issues, which has resulted in poor-quality programming,

the widely varying standard and scope of both interim and inadequate housing solutions or conflict with the regulatory

longer term housing assistance in Haiti following the 2010 authorities.

earthquake, in Pakistan following the 2010 and 2011 floods, It is alarming to note that not all the major international

and other major disasters, highlight how much more work non-governmental organisations which implement large-scale

ix