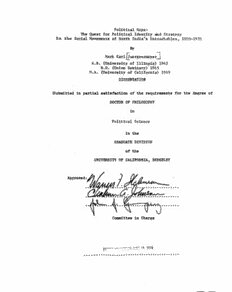

Table Of ContentPolitical Hope:

The Quest for Political Identity and Strategy

in the Social Movements of North India's Untouchables, 1900-1970

By

Mark Karl~uergensmeyer]

A.B. (University of Illinpis) 1962

B.D. (Union Seminary) 1965

M.A. (University of California) 1969

DISSERTATION

Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

in

Political Science

in the

GRADUATE DIVISION

of the

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY

Approved:

Committee in Charge

••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

c

3o

1-~_

I ~ 7J

@ COPYRIGHT 1974

Mark Juergensmeyer

'

iii

ABSTRACT:

POLITICAL HOPE: SQIEDULED CASTE MOVEMENTS IN THE PUNJAB

Mark Juergensmeyer

The focus of this study is on the Ad Dharm movement -- a

revolutionary religion of the Punjab Scheduled Castes (Untouchables)

which rose to prominence from 1925 to 1935, and was restored, in a

somewhat different incarnation, in 1970. In a larger sense, how

ever, this study examines the social and political situation of the

Punjab Scheduled Castes in this century, as a wa_y of understanding

"the politics of the poor," and the way in which social movements

are useful in strategies for change.

There are three main sections. Following a review of the liter

ature on social movements and on Scheduled Castes, the first main

section analyzes the social contexts, in two chapters. The first

chapter looks at the social ecology of the Punjab, and locates

the Scheduled Castes among the dominant Sikh, Muslim, and Hindu

religious COIIIIDWlities; the unique social characteristics of the

Scheduled Caste coaaunity are examined to determine those elements

of class consciousness and political identity which become the bases

for social movements. The second chapter looks at the social context

of the movements from a grassroots' perspective; utilizing the

anthropologists' method of field research and the sociologists'

sample survey, six local Scheduled Caste coaaunities (in three

villages, a town, and two sections of a city) are studied in depth,

to understand the role which social movements play in the lives of

ordinary people.

The second main section of the study contains, in four chapters,

a description of the historical development of the Ad Dharm movement,

based on old records and interviews. A biographical sketch is given

of Mangoo Ram, the Ad Dharm leader who had been associated with the

Ghadar revolutionary party in California. The analysis of the Ad

l)harm movement includes the origins and early leadership, the ideol

ogy, organization and social vision, and an account of the external

relations -- how the Ad Dharm responded to other social forces,

and attempted to affect change. The Ad Dharm' s relationship with

the Arya Sauj, the Congress, the British, and the Unionist Party

iv

s

a re discussed; so, also, are the movementJ relationships with

other Scheduled Caste movements -- Ambedkar' s Scheduled Caste

Federation and neo-Buddhism, mass movement Christianity, the

Sweeper movements -- and the appeals of the Radhasoami sect, and

the urban middle class. The study analyzes the Ad Dharm's demise,

and the cooptation of Scheduled Caste leadership into modern party

politics. The recent revival of Ad Dharm, in 1970, supported by

Scheduled Caste immigrants to Great Britain, is placed in the

context of the new social and political forces in the Punjab post

Independence; the study of the new Ad !harm was enhanced by field

research in England.

The third main section of the study is devoted to analysis

and evaluation, in two chapters. The first chapter attempts to

set forth a theoretical framework for analyzing and comparing the

political utility of social movements, using the rubrics of "poli

tical identity" and "strategy." Concepts from social philosophy

are borrowed to develop -a political "construction of reality" of

the poor. The framework of analysis, which is intended to be

generally applicable to the politics of the poor, is then applied,

in the last chJpter of the study, to the various Scheduled Caste

movements in the Punjab. Following the comparative evaluation of

the movements, aheomparison is also made between the effects of

government policy and thoeof social movements; the study concludes

that the unique contribution of social movements is their social

vision.

The study includes maps, tables, and the statistical results

of the study's survey. Among the appendices are included an exten

sive description of Punjab religious sects, and an English transla

tion of a 1931 report of the Ad Dharm movement.

V

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My interest in studying social movements as vessels of politi

cal change began while I was a graduate student at Berkeley. The

provocative seminars of Warren Ilchman, Chalmers Johnson, and John

Gumperz were most helpful; happily, those three influential professors

later agreed to serve as the dissertation committee for this study.

Ideas develop through discussion and critique; and for that,

I am grateful to my colleagues, Lonnie Hicks, Manoranjan Mohanty,

Emily Hodges Datta, Patrick O'Donnell and Richard Busacca. The

richness of their ideas has immeasurably benefitted my own.

I first became concerned about the situation of the Scheduled

Castes (Untouchables) while teaching at Punjab University, India,

from 1965 to 1967, under the auspices of the Presbyterian Frontier

Intern program, and the World Student Chtistian Federation. Again,

when I returned to do field research on the social movemeats of the

Punjab Scheduled Castes in 1970-71, the support and stimulation of

the academic community of Punjab University, Chandigarh, made the

st:udy possible. I am especially grateful to Prof. S.B. Rangnekar,

head of the Economics Department, who arranged for my housing, and

served with warmth and insight as my academic field advisor. Prof.

Vic tor d I Souza, head of the Sociology Department, helped me to design

the sample survey; and I am fondly indebted to my Panjabi language

tutors, Mr. Devinder Singh and Mr. Mohinder Singh, both of the

Panj abi. Department, for their friendship and assistance. Prof. and

Mrs. Eric Banerji, and Prof. Manoranjan Mohanty and Ms. Lata

Mohanty, of Delhi University, provided intellectull stimulus and

the comforts of home.

In each of the local field studies, certain individuals pro

vi.ded hospitality, made arrangements, and too~ a major role in the

study i. tself. In "Nalla, 11 it was Mohinder Singh; in "Bimla, 11 it

was Guprit Singh Dhillon; in 11Allahpind, 11 it was Principal Ram Singh,

Prof. Paul Love, and Chaplain Maqbul Caleli, all of Baring College,

Bata1a; in Jandiala, it was Santokh Singh Sangha, Avtar Singh Nahar,

and Roy Bonney; in Valmiki Gate, Jullundur, it was Hari Kishan Nahar;

and i.n Boota Mandi, it was Manohar Mahay. Their kindness will long

be remembered.

vi

\

Certain other people played key roles in my historical

I

studies of the Ad Dharm and the other social movements. I am

especially grateful to Baba Mangoo Ram, now at Garhshankar, !:hri

Mangu Ram 'Jaspal,' of Birmingham, U.K., ~ri L.R. Balley of

Jullundur, Shri Bhagwan Das of New Delhi, and Rev. Ernest Campbell

of New Delhi. I appreciated their warm hospitality, as well as

their interest in my study.

The Center for Souch and Southeast Asia Studies al the Univer

sity of California, Berkeley, has provided the necessary services

to complete the research and typing of the manuecript. I am especially

grateful for the hours of patient labor and professional skill

provided by Patrick Peel, Clinton ~eeler, Surjit Singh Guraya, and

Mary Barrett. A trip to South Asia, on behalf of the Center, allowed

me to return to the Punjab in 1973, to update my field research.

Prof. Eugene F. Ir.chick, Chairman of the Center, has been under

standing and tolerant of my neglect of Center duties in the last

hectic weeks of completing this dissertation. My work at the Center

has been made more pleasant through the cheerful presence of Ms.

Dora Austin-Doughty, Ms. Joan Platt, and Ms. Janet Hampton.

Warren Ilchman, as dissertation advisor and former Center

Chairman, has provided the intellectual challenge for this study;

as a colleague and friend, he has been gracious in his counsel, and

wise in his insight. I have learned much through the critical

perception of Sucheng Chan; she has provided for me a model of

discipline and purposeful scholarship, which impelled me to give this

study more care and concern than it might have had. To her, and

to our little friend, Ms. Brandenburg, with whom we share a home,

I a1 so owe a deep appreciation for the fullness and the <tunl .¢,

our time together.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract iii

Acknowledgements

V

Table of Contents vii

INTRODUCTION 1

A political study of social movements 1

Untouchable movements in the Punjab 3

The scholarly contexts of this study 8

Context A: studies of social movements 8

Context B: studies of Untouchables 18

1) case studies 19

2) studies of government policy 21

3) studies of social mobility 23

PART ONE: THE CONTEXT 37

CHAPTER I. 'llle Contexts for Political Action: the

Social Ecology of the Pun1ab 38

lbe context of religious rivalry 39

The context of caste: the preponderance of

Jats, and the Punjab circularity of caste 51

Punjab Scheduled Castes: the question of

inherent unity 59

a) the multiplicity of Scheduled Castes 61

b) the limits of Hindu culture 70

c) pollution and poverty: the comnon fea

tures of lower caste life 76

A caste identity beneath a caste label 79

The political coherence of the Scheduled

Castes 90

SUD1Dary 94

CHAPTER II. The Grassroots: the Punjab Scheduled

Castes in Six Local Settings 102

Village Nalla: Scheduled Castes in traditional

roles 105

Village Bimla: a perversion of the tradition 110

Village Allahpind: vestiges of social change 118

Jandiala Town: the political shape of social

change 123

Note: the Scheduled Castes of Jullundur City 130

Valmiki Gate, Jullundur: the traditional city 134

Boots Mandi, Jullundur: the progressive city 144

Suamary: the local contexts of social movements 152

PART '1WO: THE MOVEMENTS 155

CHAPTER III. Mangoo Ram and the Origins of a Revolu

tionary Religion 157

The bhakti mystique of Ravi Das 160

viii

The crystallization of consciousness 167

a) the political forces 168

b) the new leaders 174

c) the new beginnings 179

Mangoo Ram: from Fresno to revolutionary

religion 187

CHAPrER IV. Poetry and Politics: the Visionary

World of Ad Dharm 208

The concept of "qaum" 209

"Adi": myth of origins 213

Red turbans and "soham" 218

The modern virtues 224

The organizational reality 227

a) events 228

b) publications 234

c) social composition 237

d) organization 246

CHAPTER V. Ad Dharm in Motion: Points of Challenge

and Change 267

Establishing an identity, 1926-1929: factions

within, and Aryas from without 268

Securing an identity, 1929-1931: the great

census 276

Reaching out, 1931-1935: appeals for govern

ment action 282

The bold assertion, 1935-1940: Achutistan

and elections 295

The prudent assertion, 1940-1946: Ambedkar

and Unionist coalitions 299

The undoing of Ad Dharm 306

CHAPTER VI. Ad Dharm Anew: Scheduled Caste Politics

of the 1970's 325

Punjabi Suba: the new cOlllllunalism 326

Scheduled Caste politics, post-Independence 330

a) Republican Party 331

b) Christian politics 334

c) Congress 337

d) Communists 341

e) the other parties 343

The search for Scheduled Caste identity, 1970 346

a) the great middle class 350

b) Radhasoami 352

c) JD1Dary: preface to a new movement 355

f11

The new Mangoo Ram 357

Ravi Das in Wolverhampton 360

ix

Ad Dharm anew 371

a) conferences and the renewal of the

"qatDD" 375

b) strategy and the elections of 1971 379

Ad Dharm in the future of the Punjab Scheduled

Castes 386

PART TIIREE: mE ANALYSIS 406

CHAPTER VII. Politics of the Poor: the Search for an

Analytical Model 407

The neglect of the poor in political analysis 410

The group in politics -- a conceptual frame-

work 415

a) "group politics" in social science 415

b} a different kind of social analysis 423

c) an alternative model of group politics 429

Political identity of the poor 435

Strategies of the poor 441

a) the role of individuals in political

strategy 459

b) enmoacy 463

The political utility of social movements 463

CHAPTER VIII. Testing the Model: Evaluating the

Punjab Scheduled Caste Movements as Strategies 477

Evaluating the movements 483

a) Christianity 483

b) Ad Dharm 486

c) Ambedkar movements 492

d) Radhasoami 495

e) the Sweeper movements 498

f) Hindu/Sikh reform movements 501

g) nationalist movements 502

h) CoUdilunist movements 507

i) the middle class 511

Scheduled Caste strategies: the balance sheet 512

a) solidarity 513

b} aligmnent 518

c) competition 523

d) confrontation 528

e) separatism 530

f) doing the alternative 534

The movements and the government: the value

of group politics versus system politics 539

Political hope: the visionary politics of

social movements 548

The future of visionary politics 557

X

APPENDICES 567

A. Questionnaire Form 567

B. Answers to Selected Questions, Comparing Scheduled

Caste with Upper Caste Responses 578

C. Survey Questions Relating to Radhasoami (Beas), with

Percentage Response 581

D. Form for Village Information 583

E. Punjab Religiou-s Sects 586

F. Report of the Ad Dharm Mandal, 1926-!931 597

G. Magowll, District Hoshiarpur in the Ad Dharm School :

Huge Public Meeting 633

INTERVIEWS 635

A. Interviews, 1970-71 635

B. Interviewa, 1972-74 640

BIBLIOGRAPHY

642

A. Social Movanents and Political Change 642

B. India: Social and Political Change 649

C. Scheduled Castes 656

D. Punjab History, Politics and Society 661

E. Scheduled Caste Social Movements 667

F. Miscellaneous 676