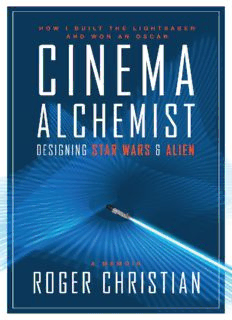

Table Of ContentCinema Alchemist

ISBN 9781783299003

eBook ISBN 9781785650857

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street

London

SE1 0UP

United Kingdom

First edition: October 2015

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TM & © Roger Christian

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at:

[email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the

Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by

any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on

the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

FOREWORD BY J.W. RINZLER

AUTHOR’S NOTE

PREFACE

CINEMA ALCHEMY

Lucky Lady—the road to Star Wars

Star Wars: how it all began

STAR WARS

Once Upon A Time In The West

Djerba

Tozeur

Final day’s prep for Tunisia

Star Wars first day shoot looms

Star Wars becomes a movie

British attitude at the time Star Wars was made

Twin suns—a hero’s journey moment

Problems mount for George

Star Wars summation

Marty Feldman’s Beau Geste and the Sex Pistols

MONTY PYTHON

ALIEN

Standby art director

Dan O’Bannon

Nick Allder and Brian Johnson; SFX

Nostromo bridge set

The crew fire up the Nostromo

Tension on the set

Ridley punches through the bridge ceiling

Jones the cat in the locker

Crew quarters

Nostromo commissary

Mother

BACK TO LIFE OF BRIAN

Back to film school

BLACK ANGEL

The script

Where do stories originate?

The true origin of my story

The script evolves

Vangelis

Giant heavy horses

Black Angel: Day 8

STAR WARS; RETURN OF THE JEDI

FINAL WORDS

Star Wars

Alien

Black Angel

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FOREWORD

BY JON RINZLER

I once came across an iconic photograph. At first I didn’t know the five people

in it, but there was an aura about the group. Sometimes an energy is present

when a photo is taken that can make itself felt many years later, even a century

beyond its time. In this case it was about thirty years later and the group soon

revealed itself to be the English art department core of the first Star Wars film:

production designer John Barry, art directors Norman Reynolds and Les Dilley,

construction supervisor Bill Welch—and one long-haired, twenty-something

who looked like he might be a visiting rock star: Roger Christian, set dresser and

provocateur.

It was Roger, in league with John Barry, who hit upon the idea of a used

universe.

This would be the ingenious answer to multiple questions, such as how on

earth could they build the visionary worlds George Lucas had dreamt up given

their inadequate budget? And how would they differentiate Star Wars from its

low-rent trashy sci-fi cousins? (2001 excepted, but that was an art film.)

Just before principal photography was to begin, almost on cue, Twentieth

Century-Fox, the very reluctant studio backer of the first film, had,

devastatingly, slashed the budget from $8.2 to $7.5 million, ten percent of which

reduction came directly out of the art department’s coffers. Christian’s work-

around brainstorm, based on years of experience under several brainy mentors,

was to source a cheap supply of odd materials, consisting of pre-fabricated

realistic shapes, forms, and ideas; that is, junk. Lots and lots of junk: airplane

junk, washing machine junk, plumbing junk. He would also sell Lucas on the

idea of real, but enhanced, weapons to stand in for the script’s blasters and

lightsabers.

I’ve written about some of this in The Making of Star Wars; it was while

doing research for that book that I found said photo, in an old binder. That book

was the best job I could do as an outsider, decades after the fact (though relying

on contemporary interviews). So when Roger told me he was writing his own

memoirs, and as I came to appreciate his phenomenal memory for both details

and the big picture, I was very excited. His account would be—and now is—the

story of someone who was right there: meeting with George in Mexico early in

preproduction; standing with him as the studio dithered, and, while prepping the

sets, watching Lucas’s back in Tunisia and at Elstree Studios. His account of the

uphill battles and challenges of the shoot are unrivaled.

Lucas rewarded Christian’s ingenuity and loyalty with matched loyalty,

helping him become a director, in turn, by backing his live-action short Black

Angel. Roger returned the favor, jumping in when needed as second-unit director

on Return of the Jedi and The Phantom Menace. In conversation Lucas would

refer to Christian, Barry, and a few others as those who had saved his quirky

little space fantasy, which no one ever dreamed would become the phenomenon

it is today (though they did think that it would be successful).

And Roger’s is more than a book about Star Wars. It is unlike any other film

book that I’ve come across in that it presents, unvarnished, the raw emotional

world of the craftspeople and artists, the producers and actors, who toil in often

impossible conditions under great duress—long hours, life-threatening sickness,

and internal foes—because they so love what they are doing.

This is never more evident than in Roger’s further adventures during the

making of the classic films Alien and Monty Python’s Life of Brian. His account

of low-budget independent filmmaking, as he cobbled together talent and

resources to make Black Angel, should be required reading for film students

(and, by the way, The Sender, Christian’s 1982 horror film, is original and scary

—and one of Quentin Tarantino’s favorites). The vicissitudes he colorfully

describes feel real; his portraits of his contemporaries are insightful and

compassionate (although a few receive naught but righteous wrath); and his

descriptions of London life during one of its creative peaks, during the 1960s,

70s, and early 80s, is a lot of fun, as he rubs shoulders with the Rolling Stones

and other luminaries.

So if you want to find out how a wily artist matched wits with the likes of

George Lucas, Ridley Scott and the Monty Python team, how integral art

departments functioned during a British heyday of film creation on the first Star

Wars and Alien, how an Academy-Award winning director crafted an enigmatic

tale from nothing, and how death was defied in devotional service to the silver

screen, then, by all means, read on…

J. W. Rinzler

AUTHOR’S NOTE

When I was having my first interview for a job in the film industry as tea boy to

the art department on Oliver!, production designer John Box gave me this

advice: “You are alone in the desert, standing next to a silver airplane with a

bottle of green ink in your pocket. A cloud of dust approaches nearer and nearer

as the director and producer arrive. The director looks at the plane and says

‘Great, this will work, can you have it red by tomorrow morning?’

You either do it or talk your way out of it there and then. That’s the film

industry.”

These wise words have served as my mantra throughout a long career and in

no small way came to full force when I was asked to set decorate Star Wars on a

budget that most people would have said, no; it cannot be done.

PREFACE

The title for this book came from my coming up with the idea to make all the

interiors of the sets and props on Star Wars from scrap metal and old airplane

parts, and being rewarded with an Academy Award for it. I signed on to set-

decorate Star Wars in August of 1975 having met George Lucas in Mexico

earlier that year while working on Lucky Lady. Being asked to come up with

props, guns and robots, new inventions in George’s script like a lightsaber,

Luke’s speeder and a diminutive robot called R2-D2 and the golden C-3PO took

a huge leap of faith and confidence. The initial budget at that time was four

million dollars and my set-dressing budget a tiny two hundred thousand.

Even at those times this was hardly enough for John Barry, Les Dilley and I to

create this world imagined and beautifully illustrated in Ralph McQuarrie’s

paintings. My first conversation with George Lucas in Mexico revolved around a

common language, that science-fiction films had portrayed unrealistic sets and

props that were all new and plastic-looking. We had a common goal—to make a

spaceship that looked oily and greasy, and held together like a very used second-

hand car. Thus the Millennium Falcon, looking like a cross between an old

submarine and a used spaceship, came about, a philosophy extending to every

detail, including the props and guns and all dressing.

My path to making Star Wars and my experiences made it possible to reach

far outside the conventional way I was brought up, and prepared me to go out on

a limb and suggest to George Lucas new ways to dress the sets, like buying old

airplane scrap and breaking it down and using it to create the Falcon’s interiors.

My pet peeve was sci-fi guns that looked and sounded like toys, so I suggested

using real guns and adapting their look for Star Wars. My luck was having a

director who was an independent filmmaker who, having made a very low

budget science-fiction film, THX 1138, did not flinch when I presented untried

solutions to the then insurmountable problem of making all the dressings and

props.

Alien was exactly the same and under director Ridley Scott I was able to take

further my ambition to make a spaceship that looked like we had rented an old

and used space truck.

Description:Christian, an Oscar-winning set decorator and director, tells the story of his breakthrough work on some iconic science fiction masterpieces of the 1970s. In doing so he delves into his relationships with legendary cinematic figures, and reveals many of the secrets of his work-- Abstract: For the fi