Table Of ContentOLIVER HILMES

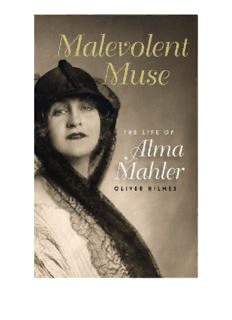

Malevolent Muse

THE LIFE OF Alma Mahler

TRANSLATED BY DONALD ARTHUR

NORTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY PRESS

BOSTON

Northeastern University Press

An imprint of University Press of New England

www.upne.com

© 2015 Northeastern University

Originally published as Witwe im Wahn: Das Leben der Alma Mahler-Werfel, by Oliver Hilmes © 2004 by Siedler Verlag, a

division of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH, Munich, Germany

All rights reserved

For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court

Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hilmes, Oliver, author.

[Witwe im Wahn. English]

Malevolent muse: the life of Alma Mahler / Oliver Hilmes: translated by Donald Arthur.

pages cm

“Originally published as Witwe im Wahn: Das Leben der Alma Mahler-Werfel. Munich, Germany: Siedler Verlag, [2014].”

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: “The legendary life of the muse of geniuses, Alma Mahler-Gropius-Werfel”—Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-55553-789-0 (cloth: alkaline paper)—ISBN 978-1-55553-845-3 (e-book)

1. Mahler, Alma, 1879–1964. 2. Vienna (Austria)—Biography. 3. Wives—Biography. 4. Mahler, Gustav, 1860–1911. 5. Gropius,

Walter, 1883–1969. 6. Werfel, Franz, 1890–1945. 7. Arts—Austria—History—20th century.

I. Arthur, Donald, translator. II. Title.

DB844.M34H5513 2004

780.92—dc23 [B] 2014038724

I should like to do a great deed.

ALMA SCHINDLER, 1898

CONTENTS

Prologue

1 Childhood and Youth

1879–1901

2 Mahler

1901–1911

3 Excesses

1911–1915

4 Marriage at a Distance

1915–1917

5 Love-Hate

1917–1930

6 Radicalization

1931–1938

7 The Involuntary Escape

1938–1940

8 In Safety—and Unhappy

1940– 1945

9 Last Refrain

1945–1964

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Image Credits

Name Index

PROLOGUE

Alma Maria, née Schindler, widow of Mahler, divorced from Gropius, widow of Werfel, was,

from early youth, an extraordinary woman, one who remains highly controversial to this day.

For one camp she is the muse of the four arts; for the other an utterly domineering and sex-

crazed Circe, who exploited her prominent husbands exclusively for her own purposes. How

can one person provoke such paeans of love on the one hand and such tirades of loathing on the

other? Was she a muse for her partners, an inspiration for their works? Doubtless that is how

she would have liked to see herself. But will this self-portrait stand up to closer scrutiny? In

1995, in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, the translator, author, and psychoanalyst Hans

Wollschläger called for a fundamental reassessment of this femme fatale from Vienna, “so that

she can be filed away once and for all. So many female companions remain silent in the

shadows of the great men in their lives, unjustifiably inconspicuous, inadequately

acknowledged; it’s time this vain, repulsive, brazen creature went in there, too.”1

Wollschläger, in his condemnation of Alma, could have referred to many judgments that

were no less negative on the part of her prominent contemporaries. For Theodor W. Adorno—

but never put in writing—she was “the monster”;2 the composer Richard Strauss diagnosed in

her “the inferiority complexes of a dissolute female.”3

The author Claire Goll wrote: “Having Alma Mahler for a wife is a death sentence,”4 an

allusion to the early demise of two of her husbands. Gina Kaus declared in an interview: “She

was the worst human being I ever knew.”5 At another point she found Alma simply “conceited

and stupid,”6 and Elias Canetti saw in her “a rather large woman, overflowing in all

directions, outfitted with a saccharine smile and bright, wide-open, glassy eyes.”7 Alma’s

fondness for drink—elegantly implied by Canetti—was likewise noted by Claire Goll: “To

compensate for her dwindling charms, she wore gigantic hats festooned with ostrich feathers: it

was impossible to know whether she was trying to impersonate a funeral horse pulling a

hearse or a new d’Artagnan. On top of that she was painted, powdered, pomaded, perfumed

and polluted. That oversized Valkyrie drank like a drainpipe.”8 No wonder, then, that this

misshapen Alma, “thanks to her exaggerated makeup and her curly-topped coiffure,”

occasionally reminded her of “a majestic transvestite.”9 Anna Mahler, Alma and Gustav

Mahler’s daughter, had a lifelong ambivalent relationship with her mother. “Mommy was a big

animal. I used to call her Tiger-Mommy. And now and then she was magnificent. And now and

then she was absolutely abominable.”10 Marietta Torberg, Friedrich Torberg’s wife, got right

to the heart of this dichotomy: “She was a grande dame and at the same time a cesspool.”11

But it is just as much a part of the phenomenon called Alma Mahler-Werfel that besides

these not exactly flattering appraisals, a number of enthusiastic, downright rapturous statements

are also on record. For her admirers, of which there were quite a few, the youthful Alma

Schindler was “the loveliest girl in Vienna.” “Alma is beautiful, is smart, quick-witted,”

Gustav Klimt rhapsodized to Alma’s stepfather. “She has everything a discerning man could

possibly ask for from a woman, in ample measure; I believe wherever she goes and casts an

eye into the masculine world, she is the sovereign lady, the ruler.”12 Oskar Kokoschka, who

entered Alma’s life a few years later, was enchanted by her. “How beautiful she was, how

seductive behind her mourning veil!”13 The biologist Paul Kammerer wrote Alma love-

besotted letters. “Your flaws are endless kindnesses, your weaknesses are incomprehensible

beauties, your languors are never-satiating sweetnesses.”14 To Franz Werfel she appeared

simply as “giver of life, keeper of the flame,”15 and Werfel’s mother allegedly called her

daughter-in-law “the only true queen or sovereign of our time.”16 The elderly writer Ludwig

Karpath assured Alma a few years before his death that, one day, “I shall take the warmest

memories of you with me to the grave.”17 Carl Zuckmayer and Friedrich Torberg admired in

Alma a “puzzling mixture of philanthropist and proprietress of a maison de rendez-vous—‘a

magnificent madame,’ as Gerhart Hauptmann once called her while admiringly shaking his

head.”18 Alma’s capacity for liquid refreshment, which many found repulsive, commanded the

high respect, on the other hand, of the no-less-capacious tippler Erich Maria Remarque: “the

woman, a wild, blond wench, violent, boozing.”19

Who was this woman, who for decades managed to fascinate or revolt so many more or

less famous people? The list of contemporaries—husbands, lovers, hangers-on, and satellites

—who crossed paths with Alma Mahler-Werfel over the course of her eighty-five years on

earth is long and reads like a “Who’s Who in the Twentieth Century.” Here is just a selection:

Eugen d’Albert, pianist and composer; Peter Altenberg, author; Gustave O. Arlt, German

philologist; Hermann Bahr, author; Ludwig Bemelmans, painter; Alban Berg, composer;

Leonard Bernstein, conductor and composer; Julius Bittner, composer: Franz Blei, author;

Benjamin Britten, composer; Max Burckhard, theater director; Elias Canetti, author; Franz

Theodor Csokor, author; Erich Cyhlar, legislator; Theodor Däubler, author; Ernst Deutsch,

actor; Engelbert Dollfuss, Austrian chancellor; Lion Feuchtwanger, author; Joseph Fraenkel,

physician; Egon Friedell, author; Wilhelm Furtwängler, conductor; Claire Goll, author; Walter

Gropius, architect; Willy Haas, author; Anton Hanak, sculptor; Gerhart Hauptmann, author;

August Hess, butler; Josef Hoffmann, architect; Hugo von Hofmannsthal, author; Johannnes

Hollnsteiner, priest; Paul Kammerer, biologist; Wassily Kandinsky, painter; Gina Kaus, author;

Otto Klemperer, conductor; Gustav Klimt, painter; Oskar Kokoschka, painter; Erich Wolfgang

Korngold, composer; Ernst Krenek, composer; Josef Labor, composer; Gustav Mahler,

composer and conductor; Golo Mann, author and historian; Heinrich Mann, author; Thomas

Mann, author; Willem Mengelberg, conductor; Darius Milhaud, composer; Georg Moenius,

priest; Soma Morgenstern, author; Kolo Moser, painter; Siegfried Ochs, conductor; Joseph

Maria Olbrich, architect; Eugene Ormandy, conductor; Hans Pernter, legislator; Hans Pfitzner,

composer; Maurice Ravel, composer; Max Reinhardt, director; Erich Maria Remarque, author;

Anton Rintelen, government official; Richard Schmitz, legislator; Arthur Schnitzler, author;

Arnold Schönberg, composer; Franz Schreker, composer; Kurt von Schuschnigg, Austrian

chancellor; Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, legislator; Richard Strauss, composer; Igor

Stravinsky, composer; Julius Tandler, physician and politician; Friedrich Torberg, author;

Bruno Walter, conductor; Franz Werfel, author; Fritz Wotruba, sculptor; Alexander von

Zemlinsky, composer; Paul von Zsolnay, publisher; Carl Zuckmayer, author.

A woman who, throughout her life, was acquainted with so many important people, to all of

whom she had something to give, even though—impressively enough—they were as different

in character as Hans Pfitzner and Arnold Schönberg, Thomas Mann and Erich Maria

Remarque, or Walter Gropius and Oskar Kokoschka. As such, she was simply destined to

become a literary cult figure. Hilde Berger wrote a novel on the relationship between Alma

Mahler and Oskar Kokoschka, and Alma fans can refer to a few older biographies as sources

of background information. It may seem surprising at first that so many writers have concerned

themselves with this woman. Unlike the men in her life, Alma has not left behind any great

artworks that might prompt us to concern ourselves with her—no symphonies, no paintings, no

buildings, no poems or novels. Clout without creativity? She may have composed some pretty

little songs as a young girl, but she has only recently been perceived as a composer.

What remains of Alma Mahler-Werfel? Is it her tempestuous life with all its ups and

downs, triumphs and tragedies, pinnacles of glory and chasms of despair? Was Alma an

authentic “life-artist,” someone who laid hands on her own story and turned it into an artwork?

Or is all that remains of her that “bit of pelvis,” as Hans Wollschläger derided her? How can

one best do justice to this woman? By letting the most intimate fount of information in existence

bubble up: and that can be found in her uncensored diary entries.

My own investigation of Alma Mahler-Werfel started out with Mein Leben—that best-

seller, which is still available at bookshops, and which left its mark on our image of Alma for

generations. The protagonist appears there as a muse and bringer of joy to her men, one who

always had to give more than she took, and a helpmate who with wise foresight chose not to

have an artistic career of her own and lived totally to support the work of her partners. These

memoirs were hailed at their release as an uninhibited confession, to which the author’s sexual

prodigality made a sizable contibution. Forty years later they strike me as being loosely

patched together and occasionally scatterbrained; worse yet, the text seems somewhat

disjointed. Conspicuously, the book is not even divided into chapters. Besides this, some

episodes are given specific dates, while others are only vaguely attributed seasonal

descriptions like “in autumn” or “at a later time.” The reader is thus not in a position to delve

into a specific point in Alma’s life; time and space blur into a diffuse generality. Interestingly,

there are no entries in the index for Adolf Hitler or Benito Mussolini, although they are

mentioned several times in the text. On the other hand, people mentioned only once are

included in the index. An oversight? Or did the author possibly have something to hide? The

sequence of compactly worded reflections followed by banal everyday lore seems to suggest

that some portions of the text were not intended for publication. On closer inspection, this

mosaic character lends the book a somewhat unintentional comical quality. Overall, I had the

impression that Alma’s confession is a diary with subsequently inserted comments. Might Mein

Leben perhaps be a version of diaries long believed to have been lost to posterity?

“If you were planning to use my mother’s memoirs as a basis for your research, then you

should forget the whole project right here and now,”20 Anna Mahler advised Franz Werfel’s

biographer Peter Stephan Jungk. The main problem of an Alma Mahler-Werfel biography lies

in the more than confusing source materials. When Alma died in New York in December 1964,

she left behind a good five thousand letters written to her, countless postcards and photographs,

as well as several manuscripts. Through the intercession of Franz Werfel’s longtime friend and

publisher, Adolf D. Klarmann, this legacy went, four years after her death, to the Van Pelt

Library at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where it remains stored to this day—

largely untouched—in forty-six archive boxes. The university quarter, on parklike grounds, is

only a stone’s throw from downtown Philadelphia. Many of the buildings on campus exude the

charm of long-forgotten times, with their typical country house architecture. Others, such as the

rather unadorned Van Pelt Library, are less inviting, utilitarian edifices. Anyone pursuing

studies of the humanities in Philadelphia is sooner or later destined to land in Van Pelt; a good

two and a half million volumes are housed in this library on Walnut Street, in addition to which

there are some thirteen thousand current newspapers and magazines from virtually every

country in the world. The quest for Alma Mahler-Werfel begins at the handwritten documents

department, which, strangely enough, is furnished differently from the rest of the library. While

the library’s façade, entrance, and catalog areas, as well as the countless magazine floors, have

the cool atmosphere of the 1960s, the sixth floor of the building, where the so-called special

collections are stored, is distinguished by massive wooden furnishings. I paid my first visit

there in the summer of 2000. I sat down at one of the tables in the reading room and waited for

the custodian of the Mahler-Werfel Collection. Diagonally across from me I discovered a bust

of Franz Werfel—a work by his stepdaughter Anna Mahler. The longer I contemplated the

artwork, the more intensely I was reminded of Elias Canetti’s not exactly flattering description

of Werfel’s “froggy eyes.” “It occurred to me,” Canetti wrote, “that his mouth resembled a

carp’s, and how well his very googly eyes fit in with that.”21 A short time later, Mrs.

Shawcross, the keeper of the collection, arrived, a lady of hard-to-determine age, pleasant and

helpful, and—a rather astonishing factor in view of her activity here—with no knowledge of

the German language. The reference guide, she warned me, was unfortunately not very reliable.

The contents had been rather sketchily inventoried several years ago, but nobody ever got

beyond that. An initial glance into the black notebook, listing Alma’s legacy, confirmed her

warning. Many of the typed pages contained handwritten additions and corrections, others

were spotted with fingerprints and barely legible, and still others were coming loose from the

binding. It quickly became clear that this reference guide would provide scant orientation, and

I would have to go through the material itself archive box by archive box. I have now done this

twice in all—once in the summer of 2000 and three years later in the summer of 2003. During

the several weeks of my stay in these special collections at Van Pelt Library, high above the

campus, under the mistrustful eye of the Werfel bust, I immersed myself deeply in Alma

Mahler-Werfel’s life. Attentive custodians, as a rule students at the university, brought me, one

after another, the cardboard cartons bearing a striking resemblance to sarcophagi—enclosing

Alma’s written remains. Countless letters came into my hands, among them ones written by

Alban Berg, Leonard Bernstein, Lion Feuchtwanger, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Gerhart

Hauptmann, Hertha Pauli, Hans Pfitzner, Arnold Schönberg, Richard Strauss, Bruno Walter,

Anton von Webern, to mention but a few. Walter Gropius’s and Oskar Kokoschka’s letters to

Alma have been preserved only as copies—the recipient appears to have destroyed the

originals. Several boxes contain innumerable photos, while still others are stuffed full of

memorabilia. In one of the boxes, I discovered Franz Werfel’s glasses, a travel alarm clock, a

letter opener, calling cards, maudlin pictures of saints, calendars, passports, baptismal

certificates, a telephone directory, and, curiously enough, one of Werfel’s cigarette holders,

complete with tobacco remnants.

Description:Of all the colorful figures on the twentieth-century European cultural scene, hardly anyone has provoked more-polarized reactions than Alma Schindler Mahler Gropius Werfel (1879–1964). Mistress to a long succession of brilliant men, she married three of the best known: the composer Gustav Mahler,