Table Of Content{- f:- i,, I

Ji..,

, 71.r -i

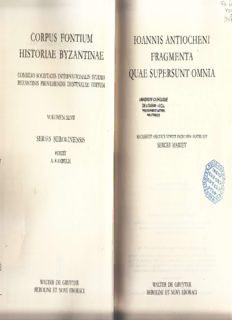

CORPUS FONTIT]M IOANNIS ANTIOCHE,NI

HISTORIAE

BYZANTINAtr,

F'RAGMtr,NTA

OMNIA

SUPE,RSUNT

QUAtr

CONSILIO S(X:II|]'ATIS INTERNATIONÂLIS STUDIIS

BYZANTINIS PROVIiHIINDIS DESTINATAE, EDITUM

UNIVERSITE CATHAL/0,UE

DE LOUVAIN . U.C,L.

PH ILæOP'IIE ET'.ETIPES

VOLUMEN XLVII q,BLIOTHEQUE

SERIES BEROLINE,NSIS RECENSUIT ANGLICE VERTIT INDiCIBUS INSTRUXIT

SERGEI MARIEV

EDIDIT

A. KAMBYI,IS

ffiiq

lra''fsE fi,ri

&+,2i."Çarr,iï'

r .9o î, ,.' t { t, !,.'... '

§ql{-fgrs!,Ë -l.i'.":,

§TAI:TIJR DI1 GRLIYT}iR §ÿAI]TER DE GRUYTT1R

IltiR()t,tNt tit' Novt titl()RACI BIIROI,INI TiT NOVI EIX)RACI

MA74e U nüne

*

@ Gedruckt auf sâutefteiem Papier,

das die US-ÀNSI-Norm über Haltbarkeit erfüllt-

rsBN 978-3- 1 1 -020402-5

Bi bliograÿrbe Infornation der Detiscben Nationalbibliothe k

l)ic Deutsche Nationalbibliothek vezeichnet diese Publikation in det Deutschcn

Nationalbibüografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet

ber hre: / / dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar.

@ Copyright 2008 by \ÿalter de cruyrer GmbH & Co. KG, 10785 Betlin

I)ieses Wcrk einschlieBlich allet seiner Teile ist uthebertechtlich geschùtzt. Jede Verwertung

aullerhalb cler engen Grenzen des Urhebertechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Vedages

unzulilssig und strâfbar. f)as gilt insbesondere für VetvielfTiltigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikio-

verfilmungcn uncl die fiinspeicherung und Verarbeitung in clcktronischen Systemen.

Printecl in Germarry

Satz: l)iirlcmann Satz, l,emfiirdc

l,)irrbanrlgcstaltung: (lhristophcr. Schncirlcr, l,aulcn

l)ruck untl buchtrindcrirche Vcrarheirung: Iluhert & (ir, (inrbl l& ür, K(i, (iiirringcn

ACIC\TO\TLEDGEMENTS

is a revised version of my Ph.D. dissertation, which was ac-

by the Ph.D. examination board of the Ludwig-Maximilians-

München on the 18th ofJuly 2005.

Ia the first place I would like to express my indebtedness to my dis-

supervisor, Prof. Dr. Martin Hose. I wish to thank him for all

understanding and advice that he provided throughout my

and post-graduate years. It was his suggestion that I followed

ing my dissertation topic and it was his support that has made

the completion of the project.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Prof. Dr. Albrecht Berger, who has

invaluable assistance at various critical moments during the

of my work. I would like to thank him for his continued con-

in my efforts, for his readiness to discuss important questions

for his help and encouragement.

§pccid thanks are due to Prof. Dr. Athanasios Kambylis for his

examination of my manuscript, for all the detailed comments

ï tuggestions he has provided and, of course, for accepting this edition

'the scries.

I em grateful to Prof. Dr. Panagiotis Sotiroudis, who graciously

photographs of all the manuscripts and commented on the vari-

rrticles I have published on this topic; Prof. Dr. Johannes Deckers

' *rc Wrein fiir Spiitantike Archiio logie und Byzantinische Kunstgeschich-

financial support during the final month of the completion of my

Prof. Geoffrey Greatrex for reading the manuscript and making

raluable suggestions; PD Dr. Kay Ehling foi assistance with the

potentates mentioned in the Chronicle; Dr. Erich Lamberz for

with manuscripts from Mt. Athos; Tobias Thumm for looking

translation; Dr. Uwe Ltick for all the software he wrote especially

thc project; Dr. Sabine Vogt and Andreas Vollmer, de Gruyter Pub-

for their efficient support; Dr. Georg Graf v. Gries for prooÊ

thc Latin indices.

I rm greatly indebted to Dr. Philip Rance for his patience and

in correcting my English translation and the Introduction. His

cxpertise and extraordinary effort have significantly improved

the tcxr.

VIII Acknowledgements

I would also like to thank all my friends and colleagues whose help TABLE OF CONTENTS

and support have very much contributed to the completion of this pro-

ject. Special thanks are due to T. Havelka, Dr. R. Knobl, Dr. K. Luchner

menrs ..... vII

and Dr. R. Tocci.

Most importantly and above all, I would like to thank Monica who

has shared with me the experience of these years. I would never have

reached this moment without her. PROLEGOMENA

Munich, October 2008 Sergei Mariev

Question.... ....4*

TheJohânnine

The Corpus .. ..... 8*

ManuscriptTladition... ...I7*

The

insidiis

Excerpta de

..........Ifi

Ex c erp ta d.e u ir tuti bas .

Codexluironÿl2.. .......20*

Suda. .......21*

ExcerptaPlanudea .;.... ..21*

The Excerpta Plaruudea and the Athos fragment . . . . . . .24*

legationibus.... ......25*

Excerptade

t . ..25*

Codex Parisinus 1630 . .

Excerptasalrnasiana. .... "26*

EditorialPrinciples ......30x

Sources ....32*

Herodian ....34*

Dio ..... "

Cassius '35*

Plutarch..... .....

'36*

Socrates ....

'37*

Zosimus. ....37*

""'38*

EunaPlus

Priscus ......40*

Candidus. .....'|. ...40*

SextusJuliusAfricanus... .......4I*

Abbreviations,... "" "43"

SclcctedBibliography,.... ""47*

x

Tâble of Contents

TEXT

IOANNOYANTIOXEô:AEANTATA:OZOMENA ANO:ITA:MATA . . . . . . . . 1

Thbula notarum in apparatu critico adhibitarum .. . ....2

PROLEGOMENA

INDICES

propriorum.

Index nominum ..469

Index verborum ad res Byzantinâs specranrium . . . . . . . . . . . 565

Indexgraecitatis.. ......571

Indexverborum memorabilium ......573

Indexfontium.... .....575

Conspectusfragmentorum.... ......583

ExcerptaSalmasiana .....583

luiron8l2.. ......583

Codex

CodexParisinus 1630. ...553

Excerptade legationibas.... ....583

Excerptadr insidiis ......583

Excerlttadeuirtutibus ....585

Excerptspknudra .......

586

Suda. .....587

Editio C. Muelleri ...... 591

Roberti

Editio H. . .. .. . .595

INTRODUCTION

€riginal text of the historical narrative conventionally ascribed to

:,fto1 the city of Antioch is lost, with the exception of one short

found in rhe Athos manuscript Iviron Br2. However, several

of excerpts composed in the tenth century or later contain

t amount of material that can with reasonable certainry be

æ deriving from this work. The evidence for the date of com-

and the character of the original work depends on rhe selection

pretation of the available excerprs.

thc second half of the nineteenth and earÿ twentierh cenruries,

id was carefully examined by a number of German and Greek

.

Their contributions to this subject constitute an impressive

rcholarly writing which evolved around the so-cailed 'Johannine

'' (a brief overview follows below). There \Àras never any question

corpus assembled by Mtiller (1851) derived from one and the

«: after the publication of studies by Boissevain (18g7) and

(1888) it was obvious to all who were involved that this was

lible assumption. The issue that \Mas most vehementÿ debated,

was which of the t'ryo parts clearÿ discernible within Mtillert

uns the authentic John of Antioch and which was spurious.

youqh the argumenrs differ in detail, two general positions clearly

Sotiriadis maintained that the genuine John of Antioch is rep-

by thc main body of the -"t.ii"l found in the constantiniàn

*

insidiis and dc uirtutibus and in the first part of the Excer?ta

This body of material will hereafter be referred to ih.

",

John of Antioch. He suggested that the second portion

Sabnasiana and the final fragments of the Constantinian

*

insidiis and de airtuübus ,puriou, on the grounds of their

. "r.

rnd. sources Patzig n"r.r qu.riioned the valiàiry of the divi_

id by Sotiriadis, but he firmly believed rhat, on the contrary,

John ofAntioch is rspresented by the second part oî the Eî-

§llm*iana and thc final fragment of the Excerpta-de insidiis and

*tlb.ru, This body of materiJ wi[ be referred to as the 'sarmasiari

ofÂntioch. §7hat sotiriadis considcrcd to be the genuine John of

\ reh wac, in Patzig's vicw, a later compilation. The m-ayoriry of schol-

4*

Introduction

Johannine Question 5*

ars, with some modifications, supported the view of Sotiriadis, while a §dmasian excerpts derive from a common source which is different

few, most significantly Gelzer, shared the opinion of Paaig. the source followed by the Constantinian fragments for the same

end (3) underlined the similarities between the Salmasian collec-

rnd the Chronicle of John Malalas.' Both Boissevain and Sotiriadis

The Johannine Question that these discrepancies make it very unlikely that the rwo col-

ultimately derive from the same work and, to different degrees,

For almost thirty years following its publication, rhe corpus of Mtiller eest doubt on the authenticiry of the Salmasian fragments: Sotiri-

(1851), which consisted mainly of the Constantinian and Salmasian considered spurious all the Salmasian material in Müller's corpus

fragments' with additions from orher sources like the Suda, remained trhc exception of fr. 1 M,3 while Boissevain expressed serious doubts

unquestioned. The debate that later came ro be known âs the "Johan- thc genuineness of the Salmasian material from fr. 29 M onwards

nine Question" Çohanneische Frage) was initiated in two publications by lffrs convinced that the Salmasian fragments from fr. 73 M onwards

Boisseyain (1887) and Sotiriadis (i888), which appeared almost simul- bc spurious.4 Alternatively, Patzig accepted the presence of the

taneously but independently of one another. Both authors pointed out a lpO diffcrent traditions in the corpus as pointed out by Sotiriadis and

number of discrepancies between the Constantinian fragments and some *bevain,r but he disagreed with the opinion that the Salmasian John

of the Salmasian fragments (the dividing line between the two parts of ântttiioocchh wwaass spurious: ffobrr Patzig, the Salmasien excerprs, rogether

the collection, the marginal note Ë'répo &p1aroÀoyio had not yet been thc fragments from Cod. Par. 1630 and the final Constantinian

discovered). Boissevain made the following observations:' (1) the same represented the original chronicle,6 while he maintained that

historical elrents are described differently in the two collections, e.g. the Çsnstantinian fragments are a later compilation.T The debate over

death of Bagoas in fr. 38 M (= EI l0) and fr. 39 M (Salm.) or the fate of corrcct identification of the genuine and spurious John of Antioch

the astrologer Larginus in fr. 107M (= EI44) and fr. 108 M (Salm.);3 (2) its zenith with the discovery of a marginal note in the manu-

the account of Roman history in fr. 1 19 - 146 M is based on Herodian, of the Salmasian collection. De Boor (1899) reported that in

whereas the two Salmasian fragments that fall into the same period fol- rnanuscripts of the Salmasian excerprs the marginal note É-rép«

low Cassius,Dio;+ (l) the majority of Constantinian fragments depend had been inserted at the end of the material corresponding

on Eutropius for their narrative framework but no traces of this author

are discernible in the Salmasian material;5 (4) the Salmasian fragments §otiriadis 1888,7-24.

contain no information on the Roman Republic, a subject conspicuously §otiriadis r888, z6-28.

§otiriadis 1888, 6.

prominent in the Constantinian fragments.6 Sotiriadis (1) investigated

Boiseevain û87, ry7f.

differences in the language and sÿe of the Salmasian and Constantinian t'§otiriadis hat sich unstreitig um Johannes Antiochenus in ganz hervorragender

excerpts;7 (2) pointed out that Leo Grammaricus, Zonaras and some of Iÿeise vcrdient gemacht: er hat das bleibende Verdienst die Gesamtmasse der Ex-

ærptc, an deren Zusammengehôrigkeit vorher niemand gezweifelt hatte, in by-

zlntinischc und hellenistische geschieden zu haben und zwar im ganzen richtig

Müller marked fr. r M as spurious. gsrchicdcn zu haben, denn diese hauptsâchlich mir Hülfe seines Stilkriteriums

This list is of course incomplete and is meant only to summarise the logic of his vorgenommene Scheidung wird durch die Quellen- und Verwandschaftsverhâlt-

arguments rather than rehearse them in detail. nirse, dic zwischen Johannes und einer gro{len Zahl byzantinischer Geschichts-

3 Boissevain û87, t62.

ehrciber bestehcn, im ganzen als richrig bestâtigt, Aber ob nun Sotiriadis nach der

4 Boissevain t887, 164. Sehcidung der Exzcrpte in zwci Cruppen die richtige von ihnen dem Antiochener

65 BBooiisssseevvaaiinn 11888877,, 1t6657.. zugewicscn hat, ist einc Fmgc, ,, " (Prrtzil; r893a, 4r5).

Iteteig rBc;e, ez.

7 Sotiriadis û88, z4-26. l'rrtrig rll,;r, r 1.

6* Introduction Johannine Question 7*

to fr. 1M. He concluded that, had this note been discovered previously, on the issue, corroborating the view that the chronicle of John of

the "Salmasian John of Antioch would never have been born".' His in- is preserved in the Constantinian excerpts and related texts. lJn-

terpretation conyinced Krumbacher (1899), who echoed de Boor with he was not able to complete an edition of John of Antioch

the words "the ominous Salmasian John can now be buried in peace", orlginally planned.

concluding that only the Constantinian excerpts remain as evidence for The publication of an edition by Roberto (2005) represented a sig-

the historical work ofJohn of Antioch. However, Patzig (1900) refused t departure from previous scholarship. This edition assembles a

to accept the newly discovered evidence at face value and the contro- nous dossier of texts including the Salmasian and Constantinian

versy fared up again, forcing Krumbacher in 1901 to suspend further similar to the edition of Mtiller, augmented with additional

discussion in the expectation that some new material would soon supply attributed to our author on the basis of parallels with either

a solution to this convoluted issue.' In writing these words Krumbacher n. Roberto tries to justify the virtual annulment of the previ-

was already aware of a discovery that had been made several years earlier ônc and a half centuries of philological research by postulating the

in a manuscript found in the Iviron monastery on Mt. Athos. It was of an anonymous historical work that was historiographically

not until several years later, however, that Lampros (1904) found time from and yet based upon the tradition of John of Antioch

to publish this unabridged fragment of the original chronicle which he trêtteva di un'opera autonoma basata sull'uso della tradizione di Gio-

had discovered. This publication was of great significance for the devel- di Antiochia."'), of which the Excerpta Salmasiana are supposedly

opment of the "Johannine Questiori'as it demonstrated that the middle Gpitome. This genealogy for the Salmasian excerpts is highly conveni-

part of the Constantinian excerpts was not, as Patzig believed, a compil- u it allows Roberto to account for the few similarities between the

ation; rather there had existed a full historical narrative from which these ian and Constantinian traditions, as well as, more importantly,

excerpts were derived. many differences that appeared insoluble to scholars of the late nine-

It is safe to conclude that not a single scholar of this period, which century. However, this solution is unacceptable for two reasons.

can without doubt be described as the acme of German Quellenforschung, there is absolutely no independent evidence that this work ever

ever admitted the slightest possibility that the Salmasian and the Con- , and so this genealogy must remain a hypothesis of its author.2

stantinianJohn ofAntioch might have originated from a common source. , even if the existence of this work could be somehow independ-

It was their unanimous opinion that the two bodies of material clearly vcrified, this would only mean that the character and implications

represented two distinct traditions. l$ "autonomy'' must be explored in full. It makes much more sense

Interest in John of Antioch and the debate over the composition !Ëconstruct this autonomous work on the basis of the excerpts from

of the chronicle was slight in the subsequent decades. It was not until Prescrved in the Excerpta Salmasiana and rclated texts (in other words,

1989 that Sotiroudis published an excellent summary of the entire schol- rËconstruct what Patzig believed to be the genuine John of Antioch)

thcn to compare the resulting corpus with the chronicle by John of

&tioch or rather what remains of it in the Constantinian collection. A

de Boor 1899, 3ot. His conclusions require a brief explanation. The portion of

the Salmasian excerpts between the title and the marginal note does not exhibit lneticulous reconstruction of this Salmasian "John ofAntioch" - not an

discrepancies with the Constantinian collection. It was the title that made scholars âll task given its numerous echoes in the later Byzantine tradition -

believe that the following material might originate from John of Antioch. The fiOuld greatly advance Byzantine studies. In any case, merging together

note discovered by de Boor indicates where the material identified in the title ends

and something different begins. Therefore, had scholars known of the note, they

I

would never have attributed the second portion of the Salmasian material to John r Robcrto zoo5, lxii,

of Antioch. A dctailcd tliscussiorr of'thc basic irssunrptions underlying Robcrtot edition is found

A note in Byzantinische Zeitschrirt ro, r9or, p. tj. itt Mnt'icv rtttl('.

B* Introduction Corpus g"

the remnants of two autonomous works so different in language, date of hevc eithet Eutropius or Herodian as their underlying source bur

composition and subsequent literary fate cannot serve as a reliable basis t1o parallels with the extânt excerpts ofJohn of Antioch. As there

for further research. Consequently, any conclusions based upon the use te â number of glosses, however, that uldmately derive from Eu-

of the entire corpus of Roberto have the potential to be distorting gen- or Herodian and correspond to the genuine fragmenrs of John

eralisations. it is safe to attribute this second group of glosses to him as

I etpecially since it can be demonstrated that the compilators of the

dld not use the original works directly (This group is designated

rEutropius"

The Corpus or "Herodian").' A third group of glosses shows parallels

other cntries in the Suda (as listed in the table below) that can be

The core of the present corpus is made of excerpts transmitted in the rffributcd to John of Antioch. One gloss explicitly names John of

Constantinian Excerpta de insidiis and de uirtutibus. The majoriry of Es its source ("Suda expressis verbis"). Afewglosses are included

these excerpts are surprisingly homogenous with respect to their language corpus because they contain language rypical of John ofAntioch.

and style as well as the selection and combination of their sources. How- ilc marked by the words "Cf. e.g.", followed by the passage in the

EI ever, three fragments from the EI must be considered spurious and ex- thrt contains similar expressions. In a few special cases (glosses

,r, cluded from the presenr corpus (3,32,33).' From the EV the following "cf. app. ad locum") the status and references to discussion of

must be rejected for the sarne reason 1,2,7,8,26 (p. 181.14-182.4)., Gtrlbution in the secondary literature should be sought in the ap-

The homogenous sequence of fragments in EI and EV extends to the loeorum parallelorum and the notes to the translation. The last

death of Anastasius I (AD 518). After a gap of about a century a few of thc table below helps to locate the sloss within the corpus

fragments relate evenrs during the reigns of Maurice und Phocas in lan- next to the passage indicates that this gloss appears in the

guage markedly different from the core of the chronicle and these musr locorum parallelorum). "Pointers," i.e. empry glosses referring

also be excluded from the corpus (EI104-110 and EV75).3 In accord- lemmata in the lexicon, are included in the table but do not

ance with these observations, the composition of the main part of the elpewhere in the corpus and are not catalogued in the cons?ectus

historical narrative is dated ro the first half of the sixth century AD. at the end of the volume.

Iviron812 In order of importance, second place in the corpus is occupied by s 527,55,11-14 Aôpr«v65 EV 35 Fr.138*

the unique unabridged fragment of the original chronicle discovered in s 971 Axp«rgvég Eutropius Fr.70

the Iviron monastery on Mt. Athos. The attribution is secure, as frag- a1043 AxvÀqTo EI 57 Fr.169.7*

Sudmae ntTs h1e7 naenxdt 1s 8o uErc1e c tohraret stpeosntifdie sto t on. lt/ho ep awssoargke so fo Jf othhnis otef xAt.ntioch is the s lla2 Iel 'l 2I 1lI ,02 2I1 ,,0 11240.-21360,3-33-,734 AAAÀÀÀééé§Ç§o«avvvôôôpppooo555 cccÊff.. aaapppppp... aaaddd lllooocccuuummm FFFrrr...222578*

Suda. Individual lemmata are attributed to John of Antioch on several e I l2l, 103.7-13 AÀé§ouôpo5 EI 12 Fr.29

considerations. Most importantly, the passages that exhibit textual sim- s 1124,103.22-3'2 AÀ駫vôpos 6 EV45 Fr. 163*

ilarities to fragments in other collections can be confidently attributed to Mquqlqs

John ofAntioch. These lemmata are identified in the table below by the e I 124, l0),32-104,2 AÀ駫vôpo5 ô EV 44 Fr. 161*

Mquqlqs

collecdon name and number. A second group comprises a few glosses

lh §otlrotrdis lg8q, t7-6q Êor Flutropius and 69-75 for Herodian.

.Ser Sotiriadis 1888, 98-ro3; Sotiroudis ry89,49 and footnote 3 on p. 16* below âl dclloor (r9:,o, rzdf.) demonstrated, thc compilators of the lexicon relied on

.§ra Sotiriadis fi88,95-99; Sotiroudis ry89,5o and foornote 3 on p. r6+ below. tlerel volunrcs of rhe Constantinian excerpta ancl on thc historical work of John

The subject is discussed in detail in Mariev zoo6, fi7-s39. sf Anrirx'h,

[0* Introduction Corpus 11*

o.1407 "AÀrretou EI 57 Fr.169.7* 61112,99.6-12 Arxtor<op EPI 5 Fr.32

a 1507 Audorq5 cf. app. ad locum Fr 145* 6 1156,104.18-30 ÀroxÀ11rr«vô5 EV 52 Fr.191*

s,1528 AupÀûvr,l ô 1000 Fr.69x a n56, r04.31-105.2 AroxÀ4tr«vôg Eutropius Fr.193

o 1685, 150.15-20 Agüooerv EPI 13 Fr.47* ô l35l Ào;retravé5 EV 33 Fr. 133*

o.1874 Aud0eor5 EI 57 Fr.169.1* 6 1352, 127.10-13 Âouerrcxvôs Eutropius Fr. 139

o.2077 , 187 .8-19 Au«ordoro5 EV 73 Fr.243* 6 1352, 127.13-18 Aouerrquôs EI 44 Fr.134*

o.2077, 187.19-27 Avcxorôoros EV 74 Fr.244* q 87 Aiôoi eixcov cf. app. ad locum Fr.7l

o. 2363, 211.14-15 AuéXer EV 40 Fr.149* or 200 AiuiÀros EV 16 Fr.82*

o. 2452, 219.14-18 Awipo5 EPI 27 Fr.73 qt 291, 177.30-32 Aipetôv EV 50 Fr. l80r

c 2452,219.18-22 Auvipa5 Eutropius Fr.74 e 281 'E4nui<»oev EV 50 Fr.180*

o.2762,247.14-248.7 Avtc.rvivos EV 42 Fr.757" e395,216j3-14'Exôr«iT qor5 EV 28 Fr.l22*

a 2762,248.18-249.3 Avr<ovivog EV 36 Fr. 140* 6 805,244.11-12 'EÀev0eprôtr15 P 246, 468.21-31 Fr.l27*

o2900,262.17-18 Arrcrvrâv EI t03,21-22 Fr. 169x e l47l 'Evteivavteg EI 87, 12-13 Fr.226*

o 3089, 277.4-5 Arrerpüezo EV29 Fr.124* e 1756 'E§qroosévov cf, Mariev (2005) Fr.l27*

o.3199 Arrrrio ôôôs Eutropius Fr.51 e 1915, 326.13 'EnayyéÀÀer cf, app. ad locum Fr.l70

a 3375,301.21-23 ArroÀapévre5 EPI 16 Fr. 50* e2241,350.14-17'ErripoÀo5. EI 22 Fr.91*

o 3416 ArroÀÀc,:vrà5 Iviron 812 Fr.98.l* 'ErrrpoÀ11

Àiuvrl e 2351, 358.24-26 'Enr«aÀôv EV 26 Fr. ll7*

o.3566, 322.31-323.7. Atrooruyoûvzeg EPI 22 Fr.60* e 2683 'Errrrriôevor5 EI 22,28-29 Fr.9l*

o.3654, 329.16-18 Arrolpqodpevo5 EV 55 Fr.196* € 3018 'EpxoüÀrog EV 53 Fr.192*

c 4316,399.17-20 "ArroÀo5 Iviron 812 Fr.98.I* E 3777, 476.7-20 Eùrpérrro5 EV 68 Fr.214*

c,4426, 412.21-26 AûOévrîJ cfl app. ad locum Fr.98.9* I 191 zuYQ EPI 16 Fr.50*

o.4458 AùpqÀrové5 EV 50 Fr. 1 80* n 500 'l-,1peito EV 29 Fr.124

a 4568 Ag'oip«zo5 cf. e.g. EV 25 Fr.115x r38 "lavo5 EI 58 Fr. 171*

o.4648 Agprxovô5 Eutropius Fr.85 I 401,638,16-639.18 'lopr«vô5 EV 64 Fr.206*

p 246,468.15-2r Beorrcrorqvés EV 30 Fr.126 t 438 'lovÀrauô5 EV39 Fr.147*

p 246,468.21-31 Beorrooravô5 Eutropius Fr.127 r 522 "lrrncxplo5 Eutropius Fr.33

p 309 BrréÀÀro5 EV 29 Fr.124* 0 517 Opvivll yro0ç q 184 Fr.4l*

p 3e6 BopiovOo5 EI 22 Fr.9l* x 119 Kq0ootoüuevos EI 57 Fr.169.4*

p 45r BouoÀoüo'xor EPI 6 Fr.21 x 122, I1.10-13 Ko0ooioor5 EI78 Fr.211x

p 536 Bpfrwov 9 184 Fr. 4 1* R391,33.24-30 K«pivo5 EV 5I Fr.188x

p 593,501.4-5 Bvpooiero5 pointer to c.4648 x l20l Kotodpera r 551 Fr. 109*

y 12,503.27-504.4 l-dïos EV 23 Fr. 111* K 1307,93.10-23 KeÀroi EPI 13 Fr.47

y 212 I-egvpi(cov Iviron 812 Fr.98.11* K 1524 Kqvoc,rp r 615 Fr.52*

y 422,538.22-23 I-po;rgorro'rri5 EV 58 Fr. 199* x 1594 Krxépcov pointer to q 567

y 427 , 539.9-r5 I-porrov65 EV 66 Fr.2l0* x 1708' 125.23-34 KÀcüôros EV 24 Fr.113*

623 Aoxio Xôpo Eutropius Fr.182 125,34-126.2 ct 5-6 KÀqüôros Herodian Fr. 119

ll2l

ô74,7.12-15 Aopeiog o. Fr.25* x 1885 Kucbooc^r À 688 Fr. 100x

ô 74,7.15-17 Aopeio5 Ps.-Symeon Fr.26 t<2007 Kéuoôos EV 38 Fr.144

ô 95, 10.14-18 Àcxviô EV5 Fr.4* R2051 KovsoüÀovs v 169 Fr.20*

ô 193 Aéxro5 EV 49 Fr.173* r2Q70 Koppivo5 EPI 13 Fr 47*

6 397 À4À«rc»p EI lOO 8r.239* K2541 KorÀlq. KoTÀov EV 54 Fr.194*

6729 Âroppriôqv Euuopius tu49 K2624 Kvrlpivog EI6 Fr. I 1*

ô 1000 Arfrye Suda expressis verbis Fr.69

6 1112,99.1-6 Atxr«rop EI 14 Fr,32*

Description:Much read in Byzantium, the historical work of John of Antioch is one of the most important, if as yet intangible, instances of the transmission of tradition in Late Antique historiography. Besides this “historiographical” relevance, the work is of particular significance as important testimony